"Daily allowances":

literary conventions and daily life in the diaries of Ida Louise Martin (nee Friars), Saint John, New Brunswick, 1945-1992

Bonnie HuskinsUniversity College of the Fraser Valley

Michael Boudreau

St. Thomas University

1 DIARIES AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL WRITINGS HAVE ATTRACTED considerable attention from scholars and publishers in recent years.1 Kathryn Carter and Margaret Conrad have assembled rich collections of women’s diary excerpts2 while Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston have engaged in the most ambitious diary project in Canada: the publication of five volumes of Lucy Maude Montgomery’s journals.3 Historians are beginning to address the complexity and value of diaries, autobiographical writings and correspondences as historical sources.4 Nonetheless, there is a tendency to privilege personal diaries as more "immediate" and "authentic" sources than published accounts such as newspaper and magazine articles.5 It must be recognized, however, that diary writing is a "complex literary . . . process".6 Diarists, like other writers, are governed consciously and unconsciously by literary conventions.

2 Diaries have taken on many different forms throughout history. In the 16th century, the literate classes used journals to reflect on public events and travels.7 Seventeenth-century Puritans and other sectarians also kept introspective accounts of their conversion experiences and spiritual growth.8 Rural folk diaries of the 18th and 19th centuries combined the traditions of the account book, the daybook, the almanac and the commercial diary: they were basically terse accounts of the daily rhythms of family and community.9 Before the mid-19th century, more men than women kept diaries, and some even had them published.10 But as the symbolic distinction between public and private grew in the late-19th century, the diary became "newly private in name" as a literary manifestation of the authenticity and unexploited purity of the private sphere. As the gatekeepers of middle-class domesticity, women took ownership of the diary-writing tradition. Personal diaries had essentially become a literary manifestation of middle-class domesticity and respectability.11 Over the course of the 20th century, a more introspective format – the journal – emerged due, in part, to the impact of Romanticism, the Industrial Revolution, the growth of individualism and developments in the field of psychology.12

3 There are many different motivations for keeping diaries. The woman writer of the 18th and 19th centuries was governed by the societal expectation that she was to "be a family historian rather than to write subjectively of the self".13 According to Margo Culley women have kept diaries in order to make time "meaningful" while Harriet Blodgett argues that it may simply be to "arrest" time, albeit temporarily.14 Perhaps recording the daily repetitiveness of women’s lives gave them a sense of permanence.15 For many authors, daily diaries were undoubtedly an exercise in charting one’s personal and intellectual growth.16 For L.M. Montgomery, journaling had multiple cathartic functions: "Keeping a diary had been a compulsion, a way to access the sheer pleasure of writing, a workshop for experiments in description, a means to escape from intolerable realities, a place to ‘consume the smoke’ of her furies, a way to record her triumphs without exposing the pride she had been taught to consider a sin".17

4 Literary scholars conceptualize the diary as a medium of self construction; according to Marlene A. Schiwy, "we create ourselves in the very process of writing about ourselves and our lives". In that sense, she argues, journal writing is "essentially a form of feminist practice".18 Post-structuralists posit that the diarist creates mutable and multiple selves. According to Margaret Turner, "a private first-person narrative is a particularly apt ideological grid for recording a subject held in perpetual conflict with itself, requiring regular revision and self-regulation".19 Painter Ivy Jacquier’s diary helped her to understand "the fluctuations of self. One never is, one has been or is becoming." As Virginia Woolf commented while reviewing her journals: "How queer to have so many selves".20

5 Many women writers have been drawn to the flexibility and elasticity of the personal diary: it can "stretch" to "meet the needs" of the writer.21 The personal diary can be kept regularly or irregularly, for long or short periods, and can be written on any surface from a commercial diary to the back of an envelope.22 Indeed, L.M. Montgomery used to write her initial thoughts on various scraps of paper, which were subsequently recopied into a more formal ledger.23 This compositional informality led feminist scholars to initially suggest that there were "no rules" governing the writing of women’s diaries and autobiographies as compared to the formal linear narratives preferred by male writers.24 It is misleading, however, to suggest that there are no organizing principles or conventions involved in diary writing. This research note will highlight the literary conventions practised in the diaries of Ida Martin (nee Friars), of Saint John, who kept daily entries from 1945 to 1992. Although she was a more modest literary chronicler than L.M. Montgomery, one can still identify various conventions in her diaries such as the use of linguistic devices, editorial interpolation and literary shaping, self-censorship, the expressive potentialities of grammar and handwriting, and the impact of diary format.

6 The diaries kept by Ida Martin are unusual because of their exceptionally long run.25 They are also significant for their periodization. Many manuscript diaries and diary collections tend to focus on the 18th and 19th centuries.26 There are also a few that cover the war years and the interwar period.27 But diaries from the post-war period in the Maritimes are sparse.28 Moreover, Martin’s diaries provides us with a glimpse of working-class rhythms; according to Bettina Bradbury, "few working-class women . . . appear to have kept diaries and few letters or other writing by such women have been preserved in archives".29

7 Ida Martin is representative of many of the female diarists uncovered by the Maritime Women’s Archives Project: a disproportionate number of these women writers were descendants of "diary-writing Yankee Congregationalists" who settled in western Nova Scotia and the Saint John River Valley.30 The Friars lineage, to which Ida Martin belongs, originated from Poughkeepsie, New York; according to a Friars family genealogy, Simeon Peter Friars left New York in 1777 (allegedly because he had deserted the rebel army and blew up one of their powder houses) to settle in Ward’s Creek, near Sussex.31 Indeed, Simeon Peter Friars is often referred to as "‘the pioneer settler of Ward’s Creek’".32 Ida Louise Friars was the seventh of ten children born to Simon Peter Friars and Louisa Maud Lockhart, the sixth generation of this branch of the Friars clan. She was born on 18 July 1907 at McGregor Brook, a few miles north of Sussex.33 Ida Friars married Allan Robert Martin on 12 November 1932 and, in February 1936, Barbara Ida Huskins (nee Martin), their only child, was born.34 When Barbara was four years old they moved from Westfield, New Brunswick, to Saint John where they resided for much of their lives.35 Ida Martin began her diary-writing career – 13 years into her marriage – on 10 August 1945. When asked why her mother began writing when she did, Barbara speculates that it may have been the need to record the excitement of the end of the war (although this is not reflected in the diaries) or her (Barbara’s) successes in elementary school. Indeed, at the back of the first volume, Martin includes a list of Barbara’s elementary school teachers. Barbara also suggests that her mother may have become fed up with "scribbling" on monthly calendars to keep track of her schedule and instead turned to diary books.36 There may be a more prosaic possibility: given that Martin began writing regularly in early August, she may have received a diary book for her birthday on 19 July. Moreover, on 10 August, Ida and her nephew left for Boston to visit her sister, so the first volume may have begun as a travel diary and then morphed into a daily diary. In any case, Martin kept her entries faithfully until mid-March 1992. On most nights she would sit at the kitchen table and make her daily entries. Her daughter recalls: "On cold winter nights I used to see her sitting with her feet resting on a piece of wood in the oven and her legs would be bright red from the heat coming out of the oven".37

8 The content and style of her entries are reminiscent of folk diaries and Victorian work diaries in their emphasis on the "exhaustive, repetitive dailyness" of rural and working-class life. The Latin root of the word "diary" means "daily allowance".38 Ida Martin’s diaries are a litany of daily labour: mostly domestic and volunteer, but occasionally paid. When asked why her mother kept her diaries so diligently, Barbara Huskins explained: "I think she had a pride in recording her life, because it was not a spectacular life, but a very ordinary, humdrum life of working in the kitchen cleaning and cooking".39 The fragmented sentence structure of the diaries resembles the account books kept by many working-class and rural women. Once considered unreliable sources, historians now realize that the value of account books rests in their "tediously pedestrian, repetitive, and detailed" structure, which reflects the lives of the women who kept them.40 One can glean a sense of Ida Martin’s daily work pattern and staccato writing style in the

following excerpt from her 1946 diary:April 30

Mailed Income Tax today. I made sand[wiches] for our class meeting at Cora’s.

May 1

Washed & ironed and just the usual work.

May 2

Cleaning all this am. I’m at Becks all afternoon.41 We went to prayer meet[ing] tonight. I went up to the Henderson’s after.

May 3

Just the usual work. I hemmed Barb’s new choir gown.

May 4

At Becks all day. Barb went to a party at Murphys. I did the Sat[urday]’s work in evening . . .

May 5

Worked at Becks all day . . .

May 6

Church and S[unday] S[chool] . Communion tonight, Mills & Verna for supper . . .It is important to note that Ida’s rhythm of work was always interrupted by Sabbath observance.

9 This minimalist writing style has been called "intensive writing", where each word carries a "large burden of information".42 In the entries for 1 May and 3 May 1946, Martin describes her domestic work routine as "just the usual work". On 4 May she records that she did the "Sat[urday]’s work in evening". Similar expressions include "cleaned all through", "worked around all day", was "busy as a bee", or worked "right out straight".43 While it is tempting to dismiss such entries as generic, they often carry more specific connotations. A phrase such as "just the usual work" takes on added significance when one determines the day of the entry. Since at least the 19th century, housework has been performed according to a daily, weekly and seasonal schedule.44 According to Barbara Huskins, Monday was "wash day come hell or high water!", with another full wash on Thursday. Some routines were daily affairs: rinsing out underwear, cooking, washing dishes and tidying up while "ironing was constant". On Saturday, the house had to be "cleaned from the outside front stairs to the outside back stairs and everything in the middle".45 There was also seasonal work, such as spring cleaning, when the family would clean throughout the house, tar the roof and take off the storm windows. During the Christmas season, Ida Martin worked "right out straight" and was "busy as a bee".46

10 Ida Martin could not personally articulate why her diaries became a key part of her daily life. When asked this question by an interviewer from the local press, she responded "[I] simply had to write in [them] every day".47 Like L.M. Montgomery, it would seem that diary writing became a compulsion for Martin.48 It is also obvious that Martin viewed the recording of family and community events to be of paramount importance. Her diaries embody the linear and non-linear components of "women’s time" and "family time": the entries record the developments of kin and community in a chronological fashion, but they also "double back on themselves" by documenting the repetitive dailyness and seasonality of domestic labour, and the recurrence of family anniversaries, birthdays and other commemorative events.49 Pages were set aside in many women’s diaries for recording birthdays, anniversaries and "Important Events". The "Forward" section of one of Ida Martin’s commercially published diaries from the 1940s recommends that the diarist use the pages in the back of the book to "list the friends with whom you exchange Christmas greeting cards".50 It was obviously assumed by the publisher that the female diarist was the keeper of family tradition.51

11 Although Martin’s diary was not officially a spiritual chronicle, it is probable that her record of daily work was an expression of her Christian faith. Like fellow Baptist Kay Chetley of Welland, Ontario, Martin undoubtedly wanted to ensure that the "grind of . . . daily work" contributed "to some greater purpose or end".52 According to her daughter, Barbara Huskins, Martin "was someone that helped out a lot of people constantly and I don’t imagine they are all reflected in the books. I remember her coming home exhausted from wallpapering Mrs. Henderson’s house, or Mrs. Todd’s house for just a ‘thank you’. . . . She was constantly making birthday cakes for all 10 Friars kids, plus a lot of others". Huskins maintains that Martin "recording these [examples of work] . . . gave her a sense of self-worth in that she was making the world (at least that person’s life) a better place. Her Christian faith certainly fit into that category because she was a S[unday] S[chool] teacher, sang in the choir, helped with Mission Band, gave W[omen’s] M[issionary] S[ociety] devotionals etc."53

12 Although Martin became a Baptist, her family history reflects the significant legacy of Presbyterianism in Sussex in the 19th and early-20th centuries. Her parents were married in the Presbyterian Kirk in Sussex in 1895 and buried in Kirk Hill Cemetery, along with most of the Friars clan.54 Ida Martin was baptized in Chalmers Presbyterian Church in Sussex in 1908 and was married in the United Church parsonage in Millstream.55 Sussex could be called a "hotbed" of Presbyterianism for many of the leaders of the Presbyterian Church in New Brunswick, such as Reverend Andrew Donald, originated from or practiced in Sussex and the surrounding area.56

13 Why then did Ida Martin eventually turn to the Baptist faith? According to Barbara, it was fortuitous. When the family moved to Saint John in 1940, Ida and Barbara stumbled into Charlotte Street Baptist Church because they were late for service at the United Church.57 Once there, Ida Martin attended Charlotte Street Baptist Church until illness prevented her from doing so on a regular basis.58 One suspects, however, that something more than mere chance governed Ida’s decision to attend and subsequently to remain in the Baptist Church. Ida Martin would have been comfortable in the company of Baptists due to their moderate theology and the long history of collaboration and cooperation with the Presbyterians in 19th-century Sussex. Mainstream theology amongst Maritime Baptists tended to focus on "personal religious experience", not on a "specific religious ideology", thus avoiding many of the theological controversies "raging" in Ontario and the West.59 Most Presbyterians in Canada had shifted away from "strict Calvinism" and so were much more open to "Bible criticism" than the American and Scottish churches.60 Thus, it is not surprising that Protestantism was marked by considerable "denominational fluidity" during this era.61 Ida’s parents reflect this legacy of pluralism: on their marriage certificate, her mother is recorded as a Presbyterian and her father as a "Free Baptist".62 For many years in 19th-century Sussex, Presbyterians and Baptists (and sometimes Anglicans and Methodists) met for services in the Roachville Meeting House until they had organized their own congregations.63 It is fitting that when Ida Martin’s mother, Louisa Maud Friars, died in 1939, her service was conducted by a Baptist pastor, Rev. Joseph Griffiths of Hampton Baptist Church, and Rev. L. Judson Levy from the Sussex United Church.64

14 Ida Martin’s decision to become a member of Charlotte Street Baptist Church also illustrates the significance of choice in determining denominational affiliation. As Hannah M. Lane has argued, "[e]vangelical church membership" was primarily a decision made by adult women like Ida. Ever since the Reformation, "women have formed the majority of voluntarist church members in churches that often offered women opportunities for expression, association, or leadership not available elsewhere".65 As Barbara Huskins recalls, by the time Ida Martin had left Charlotte Street Baptist Church after the first service, she had joined the choir and would remain active in numerous facets of church life for many years.66 In a typical month in 1946,67 Ida attended church every Sunday (Sunday School, morning service and often evening service). She also attended a women’s missionary society meeting, sang in the choir and helped with the mission band. In addition, Ida tirelessly worked behind the scenes for various social causes, including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.68

15 Ida Martin found the Baptist Church to be a vibrant spiritual and social environment. By 1901, Baptists were the single largest Protestant denomination in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. G.A. Rawlyk has referred to the Maritimes as the "Baptist heartland of Canada".69An enticing characteristic of the Baptist church is that it provided its members with an avenue for social activism. While the Presbyterians and Baptists in the Maritimes both adopted the Social Gospel, it did not establish a "strong niche" amid the former. Rather than reform society as a whole, Presbyterians were more interested in "saving the individual to improve society".70 According to Michael Boudreau, prior to 1914 the Baptists had the "richest tradition of social concern of the three principal Protestant denominations". In an effort to "preserve the church’s importance in society", the Baptists were much more adept at uniting the "sacred" with the "secular".71 A good example of this social activism is the United Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union, in which Martin was involved. Maritime Baptist women had performed missionary work overseas and at home since the early 1870s. By the post-war period, they were still involved in "projects galore", ranging from helping female missionaries in India to supporting sanitoriums in the Maritime provinces.72 As a faithful Baptist, Ida Martin would have attempted to follow the Social Gospel in whatever way she could and this was reflected in the diaries. Martin belonged to the benevolent committee at the church, often purchasing food and then packing hampers for the poor. On 20 December 1960, Pastor Armstrong of Hillcrest United Baptist Church visited Ida at home where they "talked about needy people".73

16 Although we often view diaries as spontaneous expressions of the diarists’ immediate impressions and experiences, all diaries, according to Rubio and Waterston, exhibit some literary shaping "if only in deciding what to report and what to leave out".74 While Martin probably did not engage in the degree of conscious literary pruning exhibited by novelist L.M. Montgomery, she still shaped her diary consciously and unconsciously. Thus we cannot assume that Martin’s diary, or Montgomery’s journal, will lead us closer to the "truth" about their lives. In some ways the authors’ subjectivities and the need for a "mediator" to translate the documents takes us further away from understanding a person’s life in all its nuanced richness. At best we are left with a "textual presentation" of a life. Furthermore, what are we to make of the interstices "between entries"?75 Nonetheless, one must not dismiss the importance of diaries.76 Diaries and journals, although similar to other literary forms, are distinguished by their tendency to reflect life’s "unfinishedness, its openness to unpredictable twists".77

17 A number of scholars contend that male and female diary writers construct their diaries differently. Women tend to discuss "domestic and family matters" while men record "public" affairs.78 According to feminist scholars, women’s personal diaries provide a "particular female eye through which events are viewed and which suggests that women’s position in society, their roles and their values . . . give them a unique angle of vision".79 In the muted group theory, anthropologists Shirley and Edwin Ardener assert that the dominant groups in any society determine the main forms of communication. Women, by virtue of their exclusion from power, have been forced to adopt alternative modes of communication. In other words, women have adopted diaries "to validate themselves within a culture that trivialized their lives and their writing".80 Margaret Conrad has described female diary writing as "women talking to themselves, a regular pastime in a male-dominated world where women are marginal to the discourse".81 Moreover, Margaret Turner views the very act of autobiographical writing as transgressive, a form of "self-promotion" and "empowerment".82

18 The conservative morality which infused Martin’s spiritual world led to some self-censorship in the diaries. Female diarists have often been loathe to report on "sensitive issues" related to sexuality and family scandal.83 According to Rubio and Waterston, Montgomery’s journals do not "reveal how she really saw herself in times of deep introspection and [do] not trace any traits which cast her in a truly bad light. . . . To delve into these areas would demand a measure of self-exposure that she was either unwilling or unable to undergo. . . . She constructed herself as she wanted to be remembered".84 In Martin’s family one of her nieces became pregnant out of wedlock in 1959; she subsequently left town and did not come back until she was an elderly woman. All that is recorded in the diary is that Ida’s brother was "in for most of the am telling me about [his daughter] having to get married". Seven months later, she also reports the birth of a baby boy, but nothing more.85 Similarly, when Martin’s brother and his wife separated, she writes: "Gars met me outside church with bad news of F—— and R——-".86 Anyone familiar with the family would have known the identity of F—— and R——-, but Ida Martin felt the need to be discrete. Subsequently she wrote of conversations with them and efforts to help the family, but few specific details of the break-up are given. Here self-censorship served to underscore, if not protect, the privacy of the family.

19 Because diarists and autobiographical writers of Martin’s ilk tended to avoid overt explanation and introspection,87 we must read female autobiographical writing "against the grain" – looking for female "arachnologies" or "hidden self inscriptions".88 Within these inscriptions, we can detect a deep sense of gender and class consciousness along with the conservative morality that Martin’s faith instilled within her. Some of these inscriptions can be accessed by breaking the diarist’s use of coded language. At times Ida Martin cryptically described her husband as "bad" or "terrible", and it is readily apparent that she was referring to his abuse of alcohol.89 Although she sometimes used the word "drunk", she more frequently utilized a series of indirect phrases to describe his "bad" binges: he and his drinking companions were recorded as being "on a toot", "on a bat", "caned to the eyes", "2 sheets to the wind", "souced", "tipsy" and "full, full, full, disgusting".90 At times Allan Robert, or "AR" as he was called in the diaries, was "good" or "a little ? but not too much".91 The use of question marks perhaps implies that this was a part of her husband’s behaviour that she did not wish to acknowledge or did not think appropriate to elaborate upon, even in a personal diary. Or it may simply have reflected her worry and frustration at not knowing his whereabouts during these bouts: "Allan off all day so I guess he watched TV and ?"; "Allan worked 1/2 day, got ?, and got [xmas] tree. I don’t know who with"; and "Allan terrible bad. got a roast of meat somewhere? I don’t know where".92 Ida Martin would often pace the floor at night, waiting for AR to return.93

20 Another example of a cryptic literary device used in Martin’s diaries was the use of revealing nicknames. She referred to one of her husband’s friends as "2 face" because he was Janus-faced and often took Allan away from his family.94 The most damning nickname was reserved for her sister-in-law: "Madame Queen".95 Whenever Allan visited his sister, Martin would voice her ambivalence by writing that he was "over yonder" or "over the way".96

21 Martin sometimes relegated emotional diary responses to parentheses. After Christmas in 1962, Ida wrote: "We took Grandma home (a sigh of relief)".97 After recording a dispute between AR and his sister, Ida added: "(Blamed me I know)".98 She also referred to others’ strong emotions in parentheses, such as the "(. . . heated debate)" that accompanied Charlotte Street Baptist Church’s decision in 1959 to unite with other local churches.99 Perhaps this literary technique allowed the author to have the best of both worlds: she could acknowledge that such reactions were inappropriate for inclusion in regular diary text or as a part of her daily discourse while at the same time providing her with the opportunity to vent, albeit in a more oblique fashion.

22 There were topics that Martin overtly refused to tackle, such as Allan Legere, a murderer who terrorized the Mirimachi region of New Brunswick in the 1980s. She commented in a local newspaper article, "I just thought that was so terrible what he did to those people", and she could not bring herself to record the details.100 Studying the avoidances, omissions and silences of diary texts is an integral part of autobiographical analysis: as Joanne Ritchie has put it, "we can learn as much from what people don’t say as from what they do".101

23 Despite the "gaps" and "evasions" in the diaries, there were occasional "emotional outbursts".102 At a time when respectable women were supposed to be "ever cheerful and uncomplaining", the diaries could provide, in Montgomery’s words, a "personal confidant in whom I can repose absolute trust".103 Indeed, diaries were often a safe forum for releasing tension and expressing subversive emotions and ideas "without fear of censorship or recrimination."104 Like Montgomery, who often used her journals to complain about her husband, Martin aimed a fair number of sarcastic barbs at AR. She resented the time that AR spent with friends instead of family: "Allan went over to hold Fred’s hand while we were at meeting".105 She also could not help but comment on AR’s many attempts to fix things around the house: "Usual Saturday’s work. Allan tarred shed roof, cut lawn, Broke Radio, etc".106 In April 1976, AR spent a couple of days fixing the Chevy, or "so he says".107 After running into trouble repairing the furnace in October 1982, "FINALLY he had Mr. McKenzie [fix it]. Its [sic] perfect now".108 Regarding their efforts to remodel the downstairs flat, including new bathroom fixtures, all she could say was "Oh me! Oh me! Oh me!".109

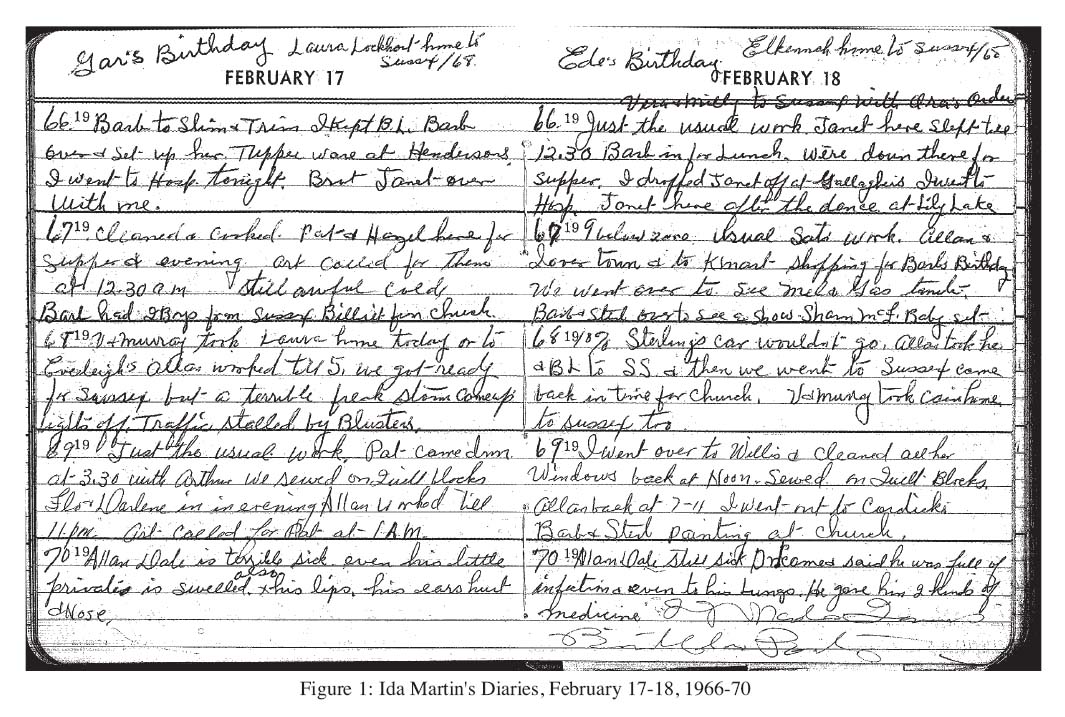

24 Martin was most explicit in her diaries about her feelings for her sister-in-law: "She’s crazy".110 And in December 1980 Martin wrote about her personal dislike of this woman: "I’m cooking this am. door opened in walked Madame Q. . . . I can’t stand her. She’s so sutble[sic]".111 Changes in handwriting reflected this enmity. Whenever Martin referred to her sister-in-law "Madame Queen" in the diaries, her handwriting became almost unintelligible (see Figure 1). It is almost as if she begrudged her sister-in-law the effort it took to write her name, let alone her nickname. The effects of emotion on handwriting is also revealed in the manuscripts of Montgomery’s novels. While writing "Mistress Pat" (1935) and "Jane of Lantern Hill" (1937), Montgomery experienced great emotional distress over her sons, her husband’s mental illness and her own depression.112 As Elizabeth Epperly notes, her handwriting was "spiky even shaky and difficult to read"; the "ink also varie[d] in flow, the writing varie[d] dramatically in slant and shape, and words [were] often illegible".113

Figure 1 : Ida Martin's Diaries, February 17-18, 1966-70

Display large image of Figure 1

25 Martin’s most troubled emotions, as revealed in her diaries, occurred after she was widowed and had to consider moving from her home to a seniors’ complex: "Sterling [her son-in-law] came up tonight and had a long talk about his house and what would be best for me. Mind is in a turmoil".114 In this sense, Martin’s prose acted "[l]ike a seismograph" (as it did in Montgomery’s journals), reflecting the writer’s "level of agitation".115

26 Aging and its attendant challenges also affected the ebb and flow of the diaries. Ida Martin wrote regularly, unless she was on vacation (which did not occur very often) or was incapacitated. The longest gap in Ida Martin’s diaries occurs between mid-June and mid-August 1986, when she became too ill to write. As Rubio and Waterston note in regards to L.M. Montgomery’s journals, "[e]ntries became shorter, to the point that they become minimal records of sleeplessness and illness". Furthermore, old age made it increasingly difficult for Martin to keep regular entries. Her last two diary volumes resemble the final entries of Montgomery. As in Montgomery’s journal, Martin’s short fragmentary entries suggest that she did not have the "energy" to "write expansively". The concluding entries lacked "any sense of shaping or final summation": there were a "few desultory entries" and then they essentially dried up. On 18 March 1992, at the age of 85, Ida Martin, like her predecessor, Lucy Maud Montgomery, "simply-or not so simply-broke off her long habit of ‘writing up’ her life".116

27 Literary scholars have shown us the importance of analyzing format and style as well as content in understanding the nature of diary writing. First, the diary books themselves must be examined. Ida Martin wrote her daily entries in commercially produced five-year volumes. These personal diaries were adapted from almanacs originally produced for farmers and businessmen. Sometimes they would include calendars, postage rates and pages at the back for records and financial statements, as well as published pages containing verses and other "cultural directives".117 In this sense, the commercially produced diary of the mid-20th century amalgamated the traditions of the working-class and rural account book with those of the bourgeois "lady’s" journal.118 A published poem in the "Forward" of Ida Martin’s 1945-49 diary implies that it was meant to be used by women to record their traditional rites de passage:What an easy thing to write

Just a few lines every night

Tell about the fun you had,

And how sweetheart made you glad.

Write about the party gay,

In the sail-boat down the bay;

The motor-trip, that perfect dance.

The week-end at the country manse.

Courtship – then the wedding time,

Honeymoon in southern clime;

Home again in circles gay,

Till ‘Little Stranger’ came your way.

So day by day the story grows

As onward your life-journey goes

Lights and shadows – memories dear,

These are MILE STONES of your career.119

28 It is also imperative to examine the diary’s "internal system of organization".120 Martin’s pre-printed volumes provided only four lines per day to record entries.121 It is probable that diarists like Ida Martin censored their entries to fit the space provided. As Cynthia Huff notes, this "tightly determined spatial format" would have controlled the diarist’s "self-expression", for it linked "account-keeping with personal reflection".122 Indeed, Ida Martin would often use the back pages of her diaries to keep financial accounts. Spatial limitation also explains why Ida Martin used marginalia and the front and back pages for additional information. On 31 December 1975 Martin used two spaces for her daily entry (since the diary had come to an end and there was additional space at the back), suggesting that she would have elaborated more often if she had been given more room.

29 Grammar is another stylistic element that one must take into account when deciphering diaries.123 There are times in the diaries when Ida Martin uses capital case letters for emphasis. She would capitalize to draw attention to transitions in the family economy: "ALLAN STARTED WITH STEPHENS [construction]", "Allan worked 1/2 day & FINISHED AT PORT", "WE PUT ON STORM WINDOWS". She would also emphasize important events, such as "CANADA 100 YRS OLD".124 Capital letters could also suggest frustration: "I went to town with M____. I sat in the car all afternoon. I was SO MAD".125 Sometimes she also used different colours for emphasis: on 2 December 1981, she wrote in red pencil: "a Red letter Day. Constitution Passed in Commons".126

30 Punctuation could be used to good effect. Inferring that Allan was a reckless driver, Martin wrote in her diary: "Allan took fill up to Wardens [in his dump truck]. Barb & I went too (we were plenty scared)????".127 One can also sense her general frustration on 20 March 1973: "AR layed [sic] under house plumbing from 7:30 till 20 to 12. Oh dear what a day!!!!! I combed Cora’s hair, I went to S Sears & Thornes. The car works terrible!!!! I could hardly get home. Stopped 15 times".128 Martin also used underlining for emphasis: "I’m so tired I layed down and went to sleep", and "Gar back in Hosp".129

31 Furthermore, intra-textual marginalia could be used to create continuity between entries.130 For example, Martin kept track of the Springhill mine disaster of 1956 in the upper margins of her diary from 3 to 5 November, which allowed her to trace the evolution of the disaster without interruption. She also used the front and back pages to reflect on events culled from the diaries. Sometimes these reflections took the form of lists of important events. These lists are interesting in that they "do not privilege ‘amazing’ over ‘ordinary’ events in terms of scope, space or selection".131 In one of the lists from the early 1970s, Martin included everything from the opening of new shopping malls in Saint John to the purchase of snow tires.

32 These lists in Martin’s diaries are also significant for their retrospective qualities. While Montgomery often ended her journals with a "climatic sweep", even writing "Good Bye" at the end of each volume,132 Martin brought a sense of closure to her five-year diaries by summarizing events in the back of each volume. Retrospection is more frequently associated with formal autobiography, but diaries are also the product of a process of recall and reconstruction. Since Martin wrote her diary entries at night, she had to assemble the day from memory, selecting the appropriate bits to record. Then she would frequently "peruse over the last years (that might be in that book) and see what she was up to a year ago or two years ago", thus reinventing the past.133 Indeed, on 26 January 1988, Martin re-read three of her diary books at one sitting.134 Like Montgomery, who also frequently re-read her journals, the reasons for doing this were undoubtedly varied. Perhaps they simply, as Rubio and Waterston note, "relished the experience" of re-reading. Or maybe it was a form of escapism, a way to "get back the spirit of youthful days". As both diarists grew older, revisiting previous entries may have provided comfort or allowed them to make sense of their lives, to discern "[p]atterns that pointed to [their] destiny".135 In any case, the relationship between the diarist and her work is obviously complex, maintains Margo Culley, as the "self stands apart to view the self" and engages in a continuous process of re-invention. There may even be a "conflation of the journal and the life itself" whereby "the persona in the pages of the diary shapes the life lived as well as the reverse".136

33 Oftentimes diarists edited their works as they re-read them; keeping a diary was a complex "re-living/re-reading/re-writing process".137 Martin changed the entries: erasing them, scratching them out and even writing over them. She pasted over her entries for 23-24 February 1970 with new commentary. There were many times when she would clarify a mix-up between entries with the use of arrows or editorial comments. On 13 October 1967, she crossed out "Gar got Lump off Elbow" and wrote "No he didn’t".138 In the entry for 13 May 1989, she notes "This should of been yesterday Fri OK?"139

34 Martin’s active engagement with the text begs the question of audience: for whom was she writing? The "importance of the audience, real or implied, conscious or unconscious . . . cannot be overstated", according to Margo Culley, for it has a "crucial influence over what is said and how it is said". The audience "becomes a powerful ‘thou’ to the ‘I’ of the diarist".140 Some diaries are written for an explicit audience, such as friends and/or family. Diaries have traditionally been semi-public documents, circulated amongst family and friends and often composed collectively: "Mothers left their journals out for the family to read; sisters co-wrote diaries; fathers jotted notes in their daughters’ diaries; female friends exchanged diaries . . . ".141 Or diarists may be writing for an "imagined future audience".142 In many cases, the audience is constructed. One could argue that "the act of writing" implies an audience of some sort, even if only the diarist or her diary: "‘Dear diary’ is a direct address to an ideal audience: always available, always listening, always sympathetic". The diary was often viewed as a confidante; some writers even named their journals.143 Montgomery imagined that her journals were "resentful when she neglected them".144

35 Ida Martin did not usually address her journals directly nor did she name them. She did, however, occasionally use her diaries to express her feelings and frustrations. But most of the time she wrote with considerable discretion. Her prudence may have been a form of self-regulation, an internalization of the mores of respectable behaviour. Or did Martin write with the realization that other eyes would be perusing her diaries? A similar question must be posed regarding her tendency to constantly re-read and revise her entries. This may be explained by the simple fact that Martin was meticulous and took her job as a self-appointed chronicler very seriously. Like Montgomery, who was concerned to "try, as far as in me lies, to paint my life and deeds truthfully", Martin also attempted to get things right: she "loved to prove things as to when they happened".145 Family members often consulted Ida Martin’s diaries to settle "kitchen table arguments" in the Huskins and Martin households. So it is probable that Ida Martin was not only writing for herself, but also for her family and perhaps for posterity.146

36 Diaries obviously share some of the characteristics of formal autobiography, such as literary shaping, retrospection and authorial intervention. While most of Martin’s diaries are written in terse, intensive language, she does at times use more formal narrative structures. At the back of the 1981-85 diary, Martin elaborated on the maladies suffered by her brother Garfield and her husband AR. Besides pulling together the relevant information scattered throughout the volume, she wrote their medical histories in a less terse and more literary style than her daily entries: "[Garfield] Operated on Tuesday 21st/81. July 28th GB called. He’s ready to come home. Called 15 min[ute]s later & said NO. He couldn’t . . . ". Moreover, her description of a car accident in which she was involved is also written as a narrative: "July 31st left Long Reach at 8pm for home. AR hit the Guy [sic] Wire of ferry floats. We both got hurt. AR chest and my face. Ambulance took us to Hosp[ital] for Xrays and we come [sic] home. Roy was right behind us. So he had car towed to his place".147 Because these incidents were so traumatic, Martin evidently thought that they were worthy of a more evocative style of expression. The inclusion of this narrative suggests, as Francoise Lionnet notes, that the personal diary is a form of metissage, embodying multiple forms, structures and autobiographical practices.148 In the words of Rubio and Waterston, diaries and journals are "partly enigma": some parts are carefully written, while others are a "tumble of unstructured responses to the immediacies of life".149

37 Diaries are complex literary sources that must be critically analyzed before historians can use them to "mine" for "information about the writer’s life and times or as a means of fleshing out historical accounts."150 But the attention is worth the effort for by embracing personal diaries we provide women like Ida Martin with agency and voice. According to Joanne Ritchie, who has also worked with the diaries of New Brunswick women, "we must acknowledge the experience of these women; we must find . . . meaning in their texts and communicate that to others".151 By conveying to others the lived experiences of women such as Ida Martin, the history and the historiography of Atlantic Canada will be enriched.

BONNIE HUSKINS and MICHAEL BOUDREAU

Notes