"Looking Towards the Promised Land":

Modernity, Antimodernism and Co-operative Wholesaling in the Maritime Provinces, 1945-1961

Stephen DutcherUniversity of New Brunswick

1 IN 1953 W.H. McEWEN, the long-time general manager of Maritime Co-op Services (MCS), the largest co-operative wholesale in the Maritime Provinces, wrote that cooperatives were not making sufficient progress towards taking "the people into the realm of Economic Ownership. Our present stage suggests that we are still in the wilderness looking towards the Promised Land, but still lacking the faith, courage and determination to go up and possess the land. We are on the march, but we haven’t really arrived".1 McEwen’s lament was understandable. When he had arrived in the Maritime Provinces from Manitoba during the depth of the Great Depression, he had brought to the Canadian Livestock Co-operative (Maritimes) or CLC (M) – the predecessor of MCS – a vision of establishing a non-profit co-operative commonwealth inspired by people such as Prairie co-operative leader Henry Wise Wood.2 For McEwen in the early 1930s, as well as those associated with the Extension Department of Saint Francis Xavier University and their soon-to-be famous "Antigonish Movement" program of adult education and co-operative action, the way forward seemed clear. The capitalist system was in crisis and near collapse, and the time was ripe for co-operatives to gain extensive control of the economy so that "the people", in the famous phrase of Extension Director Father Moses Coady, could become "masters of their own destiny".3 These co-operators and many others shared a vision that the burgeoning growth of local consumer co-operative stores, agricultural co-ops and credit unions, coupled with widespread co-operative initiatives in fish processing, housing and other enterprises, would stimulate the demand for extensive distributive co-operatives or wholesales and co-operatively manufactured goods. Co-operatives would become, at the very least, a means to create economic democracy through the widespread growth of member-owned businesses and, ideally, part of a co-operative commonwealth where the production of goods was for use and not profit.

2 Unfortunately, scholars of co-operatives in the region have paid relatively little attention to these visions of co-operatives as an alternative within or to the capitalist economy – especially in terms of the development of co-operative wholesales as the second stage in building that alternative. This is somewhat surprising since, by the early 1950s when McEwen penned his thoughts regarding Maritime co-operatives and the Promised Land, there were four co-operative wholesales in the Maritimes with annual sales totalling in the millions of dollars. Instead, scholars have focused on analyzing the origins, evolution and meaning of the famous Antigonish Movement that, by its peak in 1938, boasted 10,000 Maritimers participating in 1,100 study clubs and the creation of 142 credit unions, 39 stores, 4 buying clubs, 11 fish plants, 17 lobster canneries and 7 other co-operatives.4 These accomplishments, created in large part by a program of adult education and co-operative action under the leadership of persons such as Father Moses Coady, Father J.J. Tompkins, A.B. MacDonald, Ida Gallant and Mary Arnold, have generated a voluminous scholarly literature. Sociologists have been primarily interested in analyzing how it exemplified the characteristics of social movements in general or, alternatively, how its success was the result of capitalist underdevelopment.5 Adult educators, for their part, have seen in the Antigonish Movement a useful counterpoint to the problems of stagnation and detached professionalism facing contemporary adult education.6 And historians have chronicled the different aspects of the region’s co-operative movement while maintaining an emphasis on the central importance of the Antigonish Movement.7 Foremost among these is Ian MacPherson, who has detailed how the Antigonish Movement provided the region’s co-operative movement with much of its dynamism and how it played a major role in healing the divisions among co-operators in the region.8 By contrast, MacPherson’s coverage of co-operative wholesaling in the Maritimes – virtually the only scholarly commentary on this topic – consists of a short, general outline of how leaders within the Antigonish Movement and the Canadian Livestock Co-operative (Maritimes) spearheaded the creation of a wholesale out of the CLC(M) in Moncton with a branch operation in Sydney in 1938, how co-operators in Antigonish and Cape Breton established their own, smaller wholesales in the early 1940s, and how operations at the Moncton wholesale generated $1.7 million in annual sales by 1945.9

3 The story of co-operative wholesaling in the Maritime Provinces through the 1950s, however, is crucial to an adequate understanding of the diverse and changing nature of co-operative action in the region – one that is considerably more complex than a focus on the pre-war, social movement nature of the Antigonish Movement allows and one that necessitates an analysis of the profound social and economic changes occurring during this period.10 Ian McKay uses the concept of "modernity" to describe some of these changes in mid-20th-century Nova Scotia in terms of "urbanization, professionalization, and the rise of the positive state"; he also contrasts these changes to the reactionary efforts of some "middle-class cultural producers" to create an "antimodern" myth of an innocent, primitive and unchanging "Folk" in rural Nova Scotia in order to promote the commodification of their culture in the interests of an emerging tourist industry.11 Co-operative wholesaling in the Maritime Provinces through the 1950s, though, underscores the need to broaden the conceptualization of modernity to include economic concentration while also encouraging a wider interpretation of antimodernism. Specifically, as Maritime co-operators, through their large co-operative wholesales, strove between 1945 and 1961 to respond to the challenges of modernity, economic concentration and issues internal to the movement, the different approaches spearheaded by their managers reflected sharply contrasting philosophies, priorities and values regarding the building of the cooperative movement – differences that underlined the difficulties of achieving significant democratic economic change in the region. W.H. McEwen put his vision of the Promised Land on hold while adopting a gradualist, business-oriented approach that stressed fiscal stability and centralized control of the local co-operatives by the wholesale. Co-operators affiliated with the smaller wholesales in eastern Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island (PEI), conversely, emphasized local autonomy and the aggressive pursuit of new and expanded services to member co-operatives. Even here, though, there were fundamental differences. Island Co-op Services (ICS) on PEI embraced modernity by focussing on the rapid expansion of services through modern merchandising techniques while financing these, at least in part, through speculation on Latin American potato markets. By contrast, Eastern Co-op Services (ECS) in Antigonish and Cape Breton Co-op Services (CBCS) in Sydney, which were closely associated with the Antigonish Movement, combined an emphasis on modern marketing and production technologies with a renewed emphasis on the movement’s Christian, agrarianist antimodernism and its celebration of rural, pastoral life.12

Early Co-operative Wholesaling

4 Co-operative wholesaling, which originated in mid-19th-century England with the flourishing of the first modern co-operative in Rochdale and associated co-operative societies, was predicated on two different rationales: competitiveness and a social vision.13 The creation of second-tier, co-operatively owned distribution enterprises was necessary from a business point-of-view because of the need to provide economies of scale as well as to secure unadulterated goods at fair prices for the burgeoning number of local co-operatives – something that many local co-ops were unable to obtain from private wholesalers who often had ties to the co-operatives’ competition.14 Co-operative wholesales were also regarded as an essential component of fulfilling the social vision of co-operatives as the second step or stage in the development of an alternative to an exploitative capitalist economy. At the very least, the widespread extension of co-operatives in the economy would act as a corrective to unfair competitive practices by capital-based enterprises by providing a democratically controlled alternative for producers and consumers; ideally, the extension of co-operatives into virtually all sectors would generate a new type of economy and society – a "co-operative commonwealth" – where co-operatives would be the dominant type of business and social relations would feature economic freedom, solidarity of labour, "production for use, not profit", the abolition of child labour, free education and industrial and political action.15

5 This dual purpose of co-operative wholesales was a dominant feature of cooperative action that spread to Europe and North America during the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Yet early attempts by farm organizations in Canada to operate large, centralized wholesale operations either failed or encountered severe difficulties before achieving success. The hastily built and overextended United Farmers cooperatives in Ontario and the Maritimes were unable to withstand the post-First World War recession and over-extension of resources which plagued their operations. The co-operative wholesales on the Prairies, after struggling through the early years of the Great Depression, successfully diversified into such areas as petroleum production and groceries during the 1930s and feed, coal mining, lumber, hardware and clothing by the 1940s.16 Between 1945 and 1955, sales for the three Prairie wholesales, bolstered by the formation of hundreds of new co-operatives, more than tripled. Many new staff and managers were hired, including a significant number from the private sector, as business operations became more systematic and professional. The three wholesales eventually merged: Saskatchewan and Manitoba amalgamated in 1955 to become Federated Co-operatives Limited, which in turn absorbed Alberta Co-operative Wholesale Association in 1961 to prevent the Alberta wholesale from going under.17

6 In the Maritime Provinces, the move to establish a broadly based co-operative wholesale began in the mid-1930s. The dire economic straits caused by the Great Depression and the lack of a social safety net, together with the enthusiasm generated by the Antigonish Movement, produced nearly 40 new consumer co-operatives – cooperatives in need of an alternative supplier to that of the privately owned wholesalers. There was also the need to diversify and bring in additional income to the Canadian Livestock Co-operative (Maritimes), the central marketing co-operative for the many local livestock shipping clubs in the region. Prince Edward Island producers had left the organization in 1933, taking with them their yearly $500 grant from the PEI government (20 per cent of the central’s annual budget) because of a disagreement over whether the focus of the CLC(M) should be livestock marketing or livestock marketing and feed production.18 Lastly, two of the major "co-operative" organizations in the region were headed by staunch advocates of the idea of cooperative wholesaling as the second stage in developing co-operatives as the dominant form of business enterprise. W.H. McEwen, general manager of the CLC(M), was steeped in the Prairie notion of the co-operative commonwealth, which envisioned the end of the competitive, profit-driven and exploitative capitalist economy in Canada through such initiatives as the elimination of private banks (and interest charged on credit) and the replacement of "the profit system with a nonprofit co-operative commonwealth" where "the motive of business is founded on fair and equitable service to all, instead of greed and selfishness, . . . where the Gold[en] Rule can and will work". Co-operators had to continue to build strong local co-operatives as well as establish wholesales; these wholesales would "in turn co-ordinate their efforts to go on to the control of manufacturing and industry".19 Father Moses Coady, director of the Extension Department at Saint Francis Xavier University, had a similarly broad vision of co-operative development through local co-op stores, credit unions and other co-operatives: "When the people own, cooperatively, enough of these institutions and when the volume of demand grows, they can federate into wholesales and either build or take over the manufacturing plants in the distant industrial centres". Once this was done, "the people" will have gained "control and ownership of the productive processes in modern society".20

7 It was the Canadian Livestock Co-operative (Maritimes) and the Extension Department that spearheaded the establishment of co-operative wholesaling in the region. By 1934, McEwen had begun to articulate in the pages of The Maritime Cooperator and at various meetings a plan to implement co-operative wholesaling through an amendment the CLC(M)’s constitution so that the organization could "engage in the co-operative buying or selling of feeds, flour, seeds, insecticides, rope, twine, tools, fertilizers and any other good or machinery used in the production, processing or manufacture of farm or other primary products" as well as "general merchandising". McEwen, in addition, proposed the promotion of urban cooperatives, arguing that only when "both rural and urban workers" were "organized to handle their own business" could they create "a democratic society where the Cooperative motto of ‘Each for all and all for each’ will be a pleasant reality".21 McEwen and A.B. MacDonald, the associate director of Saint Francis Xavier University’s Extension Department, conducted a survey of all local co-operatives in eastern Nova Scotia to ascertain the extent of their interest in a wholesale and took a leading role in a committee examining the establishment of such a wholesale – made up of representatives from the CLC(M), the United Maritime Fishermen, the Pictou United Farmers and the British Canadian Co-operative (BCC) in industrial Cape Breton. McEwen and MacDonald were also key speakers at two large meetings in eastern Nova Scotia in 1937 (in Judique and Sydney) to address the apprehension of many local co-operators about establishing a co-operative wholesale. These concerns included a lack of ability to commit to supporting a wholesale (i.e., too small a co-op to order railcar loads), complaints over product quality, concerns over the distance of the CLC(M) in Moncton from eastern Nova Scotia and particularly the unwillingness of some local co-ops to forego to opportunities to seek cheaper prices from non-cooperative distributors. In the latter case, for instance, the manager of the large British Canadian Co-operative maintained at the Sydney meeting that his co-operative’s immense size meant that it received wholesale prices from manufacturers already and that it would only support a co-operative wholesale "if prices were equal or nearly so".22

8 By the spring of 1937, the only major co-operative organizations still involved in co-operative wholesaling were the CLC(M) and the Extension Department. In response primarily to A.B. MacDonald’s prodding, a resolution was drafted and presented at an April follow-up meeting in Sydney that a wholesale be established in eastern Nova Scotia, that all local co-operatives be members and that the wholesale be guided by the board of directors of the CLC(M) in Moncton and an advisory committee consisting of one representative from each local co-op in eastern Nova Scotia.23 The resolution passed unanimously despite an often-lively debate concerning the ability of "a bunch of farmers" to organize and run a large co-operative wholesale.24 The wholesale in Sydney opened on 1 October 1938 and during 1939 did approximately $30,000 in sales per month.25

The Challenges of Modernity

9 The advent of the Second World War in 1939 had a paradoxical effect upon the wholesale’s operations. Despite wartime restrictions, annual sales at the wholesale blossomed to $1.7 million by 1945, an increase more than matched by remarkable growth in the CLC(M)’s livestock marketing due to wartime "Bacon for Britain" contracts.26 Yet these gains during the war years also encouraged some co-operators in the region to form their own smaller co-operative wholesales instead of working within the CLC(M) itself. Eastern Co-operative Services was established in 1940 around the Antigonish area to serve area farmers and by 1945 had annual sales of $286,000. Cape Breton co-operators, unhappy from the beginning with their branch status within the CLC(M), followed suit in 1941 and established Cape Breton Co-op Services; this smaller co-operative wholesale, however, remained affiliated with the CLC(M) and by 1945 had annual sales of more than $1 million.27 This splintering of co-operative wholesaling efforts within the region, and the consequent loss of efficiency and economies of scale, was offset somewhat by the establishment in 1940 of Interprovincial Co-operatives Limited (IPCO), a third-tier, national distribution and manufacturing co-operative whose membership eventually consisted of cooperative wholesales across Canada and that provided the "CO-OP" brand of goods nationwide.

10 The war years also ushered in increasingly rapid and systemic changes arising from what Ian McKay calls "modernity" or "urbanization, professionalization, and the rise of the positive state", and these changes greatly intensified during the post-war era.28 Outmigration by Maritimers, urbanization and the rapid decline of "family farms", for instance, led to a dramatic decline in the rural population. The number of primary producers in the Maritimes fell by more than 50,000 between 1951 and 1961, with the largest decline in agriculture (49 per cent) followed by fishing (37 per cent). The total number of people remaining on Maritime farms also fell significantly over the same period: 49.7 per cent in Nova Scotia (115,414 to 58,020), 57.8 per cent in New Brunswick (149,916 to 63,334) and 25.8 per cent on Prince Edward Island (46,855 to 34,753). Approximately 82,000 people left the region during the 1950s while employment in government service (excluding the armed forces) and the service sector increased by more than 42,000.29

11 The state also became more activist in the economy during the 1940s and 1950s through the production of goods for the war effort, the introduction of social welfare programs such as Unemployment Insurance (1940), Family Allowance (1944) and a modernized Old Age Security (1951), and involvement in efforts to promote economic development.30 Yet this state activism also served, in many instances, to undercut small producers and their efforts at co-operation; the improved economic climate from the general upswing in economic activity and wages for Maritimers as well as the extension of social welfare programs helped to lessen the perceived need for co-operative action among many Maritimers.31 While some government officials remained sympathetic and active in their support of co-operatives, such as S.W. Keohan, the registrar of co-operatives in New Brunswick, J.C.F. MacDonnell, a provincial agricultural representative in eastern Nova Scotia and F.W. Walsh, who eventually became Nova Scotia’s deputy minister of agriculture, most government officials became more "professional" and lost interest in the problems facing just small producers. Sometimes this resulted in hostile initiatives, as in the 1943 federal government’s attempt to tax the patronage rebate that co-operatives returned to their members; for W.H. McEwen this attempt to tax rebates, together with wartime restrictions on the growth of co-operatives, were "[the two] jaw[s] of the bureaucratic pincers to destroy the co-operative movement".32 In the post-war era, the "professionalization" of the burgeoning bureaucracies continued as personnel and programmes became even less oriented to the needs of small producers and more towards large, private businesses within the context of the prevalent "free enterprise" post-war ideology.33 Modernization through capital-intensive mega-projects involving large capital-based enterprises and financial incentives exemplified this shift in the approach of government during the 1950s (or the "Decade of Development") as did the creation in New Brunswick of agricultural policies favouring agribusiness interests such as McCain and in Newfoundland of fisheries policies benefitting large corporations and the frozen-fish trade.34

12 One aspect of change not accounted for in McKay’s conceptualization of modernity, though, is the economic changes taking place at the time.35 Increased corporate concentration in, for example, the retail/wholesale sector was well underway by the early 1940s. The national chain Dominion Stores entered the Maritimes and brought the self-serve "Super-Markets" that had, according to Gus MacDonald, a prominent Halifax co-operator, loss leaders, "the gleaming hygienically clean (no sawdust on the floor) meat department", bulk items placed near the exit and "a smiling ‘bagger’ to carry bags to vehicles".36 Although co-operatives tried to counter with a more "professional" approach (i.e., the addition of "field representatives" to assist managers of local co-ops, the formation of system-wide committees to oversee hiring and dispute resolution, and training for store employees "in co-operative philosophy and modern business technique"), the 1950s brought even tougher competition in the retail sector from Dominion Stores and newer enterprises such as IGA and the regional retailer Sobeys.37 Moreover, there was an accelerated trend towards vertical and horizontal integration amongst large corporate interests such as Canada Packers and others involved in livestock, feed and other commodities, a situation that made it increasingly difficult for the co-operatives to effectively compete.38 Even attempts to create vertical and horizontal integration within the cooperative movement had a detrimental impact on the development of the movement in the Maritimes as the increasing success of Interprovincial Co-operatives – the third-tier co-operative established in 1940 to help co-ordinate the co-operative buying, distribution and manufacturing of goods on a national scale – served, at least in part, to undermine the need for further inroads in distribution and especially manufacturing within the region. By 1948, IPCO enjoyed annual sales of more than $4.4 million while also establishing a bag factory in Montreal; it marketed many types of goods under the CO-OP label such as "car, radio, and flashlight batteries; binder twine; brooms; grain grinders; milking machines; oil and greases; shingles; turpentine; and washing machines" as well as distributing co-operatively produced flour out of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool Mill, products from the accompanying flax-crushing plant that opened in 1949 and, from 1951 onward, coffee and tea from a co-operative processing operation in South Burnaby, British Columbia.39 Aside from some small-scale co-operative manufacturing of feed, however, relatively little was achieved in the Maritime Provinces.

Maritime Co-op Services

13 Co-operative leaders within the different co-operative wholesales in the region responded differently to these far-reaching challenges, in part as the result of sharply contrasting philosophies, priorities and values regarding the building of the cooperative movement and also because of the differing economic performance and results during the post-war years and through the 1950s. Maritime Co-operative Services, for instance, the new name of the former CLC(M) from 1944 onward, enjoyed considerable growth in its operations during this period. The number of employees grew from 50-60 "regular" employees in 1945 to more than 100 by 1951. Physical facilities expanded significantly in 1946 with the purchase for $20,276.76 of eight buildings used in the war effort. Several new departments, including an insurance department in 1949, were added to the existing livestock, grocery-machinery and feed departments. Membership from local co-operatives, agricultural societies, fishermen’s co-operatives, livestock shipping clubs and rural and urban buying clubs reached 210 by 1949, with 15 of these joining during 1948-49. The smaller co-operative wholesale affiliates of MCS – Eastern Co-op Services and Cape Breton Co-op Services – were joined by Island Co-op Services in 1949, which had been established on Prince Edward Island by six local co-operatives that were members of Maritime Co-op Services.40 MCS also built on ties with the emerging Newfoundland co-operative movement begun in the early 1940s; by the late 1940s, there were 30 co-operatives operating in Newfoundland with 20 more in some stage of organizing. These 30 co-operatives, in a six-month period in 1949, conducted more than $30,000 of business with MCS out of Sydney and, by 1950, five Newfoundland cooperatives, including Gander and Cornerbrook, had become official members of MCS.41

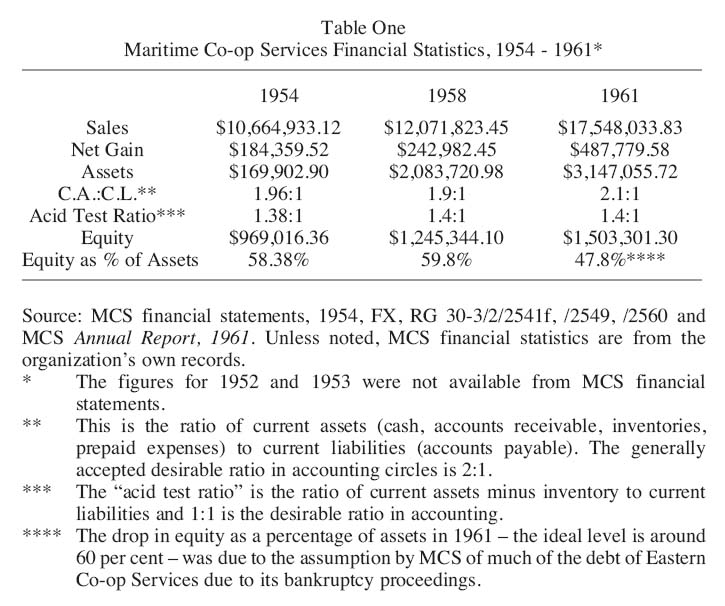

14 Financially, MCS operations showed steady progress. In the immediate post-war years, annual sales of MCS increased on a regular basis: $3,214,968.20 (1946), $4,022,807.95 (1947), $6,677,762.20 (1948), $7,904,854.30 (1949), $8,841,315.72 (1950) and $10,577,238.83 (1951). Accounts receivable remained fairly constant between 1947 and 1951, increasing from $445,699.99 to $653,422.42, while inventories rose from $78,329.34 to $116,704.50 over the same period.42 Throughout the 1950s MCS maintained its focus on continuing its gradual and steady growth.43 As can be seen in Table One, annual sales and other, more in-depth financial indicators continued to climb consistently between 1954 and 1961 while equity levels, the ratio of current assets to current liabilities and the acid test ratio (current assets minus inventory to current liabilities) remained near or above generally acceptable levels.

15 Despite this growth, the MCS board of directors and management continued to follow their long-standing conservative approach to the promotion of sales and cooperative development. MCS had a policy against competitive advertising because of its gimmickry and cost, and this policy remained despite an attempt in 1954 by PEI board member Arnold Wood to overturn it. Wood argued that "advertising was desirable", that Cape Breton Co-op Services used radio advertising through CJFX, the radio station in Antigonish, and that MCS should advertise as well. Yet even though some of the other board members admitted that the co-operative movement owed something to CJFX, which had done much to promote co-operation in the Maritimes, the board as a whole re-affirmed its stand against competitive advertising and published a pamphlet later that same year re-iterating its position.44 Maritime Co-op Services also continued to avoid credit; not until the early 1960s was its traditional position against extending credit to individual co-operators relaxed when it became apparent that providing credit would be the only way by which co-operatives could sell large consumer goods such as appliances.45 The management and board of MCS were also reluctant to become involved in new ventures. They turned down a proposal in 1951 from outside the organization that MCS become involved in the marketing of wood products.46 The MCS board also turned down several new initiatives proposed by member co-operatives. In 1949, it took no action on a proposal by members of several Saint John River co-operatives that MCS becoming involved in the mixing of insecticides.47 The MCS board and management rejected a proposal that MCS become involved in the marketing and processing of fruits and vegetables as well as a subsequent appeal that MCS become involved in only the centralized marketing of agricultural commodities as a means to increase agricultural production in the region. In the latter case, the MCS board suggested that this "could best be accomplished" by some of the larger local co-operatives and that "Central did not fit in the marketing scheme at this time".48 The MCS board was even not adverse to pulling out of ventures that had already been approved by the membership at its annual meetings; despite delegate approval at the 1951 annual meeting for the construction of a feed mill in Devon just outside Fredericton, general manager McEwen reported at the 1952 meeting that the board had decided not to proceed with the construction of the mill because it was felt the existing co-operative mill in northwestern New Brunswick "was in a satisfactory position to render the service there for parts of New Brunswick".49

Table One : Maritime Co-op Services Financial Statistics, 1954 - 1961*

Display large image of Table 1

16 The board and management’s conservative approach to co-operative development and their pre-occupation with fiscal stability led to a rift with MCS member co-ops that manifested itself most tellingly at the 1956 annual meeting. Near the end of the meeting, a resolution was presented criticizing the MCS directors and, by implication, also management who had "been so preoccupied with material and financial considerations at their meetings as to overlook the element of Christian love and charity which motivated our Movement in earlier days" and, consequently, had made no response to assist the families of the miners lost in the Springhill disaster "only seventy miles from our headquarters". The motion, which passed by a standing vote of 45 - 2, called on the MCS board to "re-examine its attitude in this regard and make such contribution in some practical way towards our Springhill brethren as they may see fit, and furthermore, that our Board continue to be alert to opportunities for service to our fellowmen other than in the necessary but more materialistic, commercial operations of our organization".50

17 MCS’ cautious, conservative approach to co-operative development is perhaps more understandable when put within the context of some of the struggles facing the organization during the post-war period and the 1950s. MCS had almost been cut out of the feed business, one of the most stable and profitable aspects of its operations, in the post-war years when capitalist firms regained control from government of the grain supplies and private agents were once again able to make side deals with individual local co-operatives. The 1950s saw the rise in popularity of "buying clubs" in the Maritimes where members pooled their resources to obtain better terms of sales on various goods. Characterized by a lack of solid management and little or no equity, W.H. McEwen viewed these clubs as a threat to local co-ops in that they did not contribute to the building of the co-operative system, they sapped the energies of cooperators and they allowed private wholesales to weaken both local co-operatives and MCS by offering the clubs artificially low prices. The biggest struggle facing MCS, however, was the lack of consistent and full support and patronage of MCS by the local co-operatives and the smaller wholesales that often looked elsewhere for cheaper-priced goods.

18 In 1946 McEwen put forward his "Maritime Plan" to try to address this growing problem through "orderly development". All local co-ops would have to submit to a "management agreement" whereby supervisory authority would be delegated to MCS, local co-ops and smaller wholesales would have to patronize all MCS departments fully, each local co-operative’s membership in MCS would be contingent upon meeting these conditions, no new co-ops would be started without the approval of an MCS area supervisor, and MCS would manage the whole system and provide centralized audits and financial plans. The delegates at the 1946 annual meeting, however, tabled the plan for further discussion; the delegates at the 1947 meeting did likewise, with the additional stipulation that a questionnaire be sent out to all local coops (five were returned). While the plan was not even discussed at the 1948 annual meeting, by the mid-1950s many of the local co-operatives were facing severe problems. A resolution passed at the 1955 annual meeting called for the MCS board of directors and management "to go ahead as they see fit with a plan whereby desirable supervision and guidance be extended to any co-operative associations affiliated with our Central". McEwen sent out a letter to all local co-operatives detailing the conditions for entering into a management agreement (i.e., there had to be 15-20 co-ops within a reasonable distance of each other), and he received a large response as many co-operatives were in trouble. By late 1955, McEwen had drafted up a standard management agreement form – despite pleas for special consideration from numerous local co-ops – and within a short period many had signed on. Yet while these local co-operatives had been forced into a co-ordinated and centralized system in order, in McEwen’s words, "to bring the movement the strength of a chain", the smaller regional wholesales in the Maritimes were another matter.51 The struggles of Island Co-op Services, Eastern Co-op Services and Cape Breton Co-op Services were to dominate the co-operative wholesaling agenda in the region from 1955 until the 1960s.

Island Co-op Services

19 Co-operators in Prince Edward Island had a quite different experience with cooperative wholesaling. PEI co-operators had left the CLC(M) in 1933 after a dispute over the location of the head office and the issue of whether the association was primarily a livestock marketing organization or one that should also devote attention to the animal feed business.52 By 1946, conditions were conducive to the formation of an Island co-operative wholesale: the six local consumer co-operatives had a membership of 2,500, private wholesalers were charging the co-operatives "just a bit more than they were selling to their competitors" and, although CO-OP brand products were becoming available to co-op member across Canada, there was a lingering resentment against the CLC(M)/MCS and an unwillingness to access these goods through it.53 It was not, however, until the 1949 annual meeting of the Co-op Union of Prince Edward Island that action was finally taken as slumping crop prices and an opening address by W.H. McEwen spurred PEI co-operators to establish Island Co-op Services or ICS.54

20 The co-op union president, Jerome O’Brien, who was also assistant manager at Morell Co-operative, relinquished both of these positions to become the general manager of ICS.55 Both O’Brien and his colleague Frank Dunn had studied at Saint Dunstan’s University in Charlottetown under "the apostle of the Antigonish Movement on the island" J.T. Croteau, and O’Brien spent several months after he graduated in 1937 promoting the Antigonish Movement in King’s County before he and Dunn began organizing study clubs around the Morell area as well as a credit union, a co-operative buying club and, by 1940, a co-operative store where Dunn served as the first manager.56 ICS was "a multipurpose organization" that not only acted as a marketing organization for the produce – especially potatoes – of producer/members of the local co-operatives but also sought to supply the local cooperatives with merchandise. ICS grew rapidly during the early 1950s, securing sales exceeding $1,000,000 in its first seven months alone.57 By mid-1950, ICS had expanded into groceries when it bought out N. Rattenbury Limited, a local wholesale company. This move enabled it to offer, on a limited basis, "groceries, butter, fish and other agricultural and fish products, in addition to potatoes, seed, and live stock feed" to its 33 member co-operative associations.58 By 1952, ICS had expanded from the initial two employees in 1949 to a staff of 20 and annual sales went from $700,000 to $3,000,000. It handled some 800 carloads per year of potatoes and turnips for the 18 consumer co-ops on PEI while adding new departments to the existing produce and wholesale departments: a plumbing and heating service to assist member co-ops such as "the ultra-modern, $80,000 Co-op store . . . constructed at O’Leary" and an insurance department that from July to December of 1952 had "written approximately one million dollars of fire and casualty insurance". In total, besides the 18 co-op stores associated with ICS, there were seven canneries, five creameries and eight frost-proof potato warehouses.59 By early 1953, ICS had purchased and taken over the Swift’s poultry processing plant in Charlottetown; the plant included "a new, modern chick hatchery, an egg-grading station, refrigeration rooms, a poultry killing plant, and warehouses", and all ICS operations were moved to the new location.60 By the spring of 1955, ICS officials were planning to create a new subsidiary company – Island Farm Services – which "would freeze and can vegetables, fruits, meat, and fish". The provincial government had agreed to invest $1 million in the project.61

21 ICS, however, faced several serious problems during this period of rapid growth. Some local co-operatives did not pay their accounts for goods received from ICS for months at a time – a situation compounded by the lack of "a permanent cash trading policy" and resultant credit buying by the locals.62 The grocery wholesale ran a deficit every year from the time of its establishment, yet the efforts on several occasions by the ICS board of directors to close it were stymied by the promises of greater support from the large local co-operatives.63 These same locals would often use ICS as a bargaining tool in negotiations with private suppliers, with one co-operative, Central Farmers in Charlottetown, even creating its own rival wholesale.64 Personnel problems at ICS were allowed to fester unresolved and led to a situation where "directors resigned giving little or no reason, senior staff members who spoke out were either fired or told to go if they were not satisfied with things as they were, while member co-ops withdrew their patronage and support".65 Member co-operatives had levels of equity in ICS far lower than the generally desirable 60 to 70 per cent; member equity declined from 40.3 per cent in 1953 to 31.4 per cent in 1954 and, although it recovered slightly by January 1955 to 35.4 per cent, by June 1955 equity had fallen to 6.3 per cent.66

22 The main cause of this drastic decline – and of the crisis that spelt the end of ICS in August 1955 – was potato marketing. Contrary to the generally accepted cooperative principle of limited return on investment, ICS management had instituted, over the objections of some Island co-operators, a system of buying members’ products outright and then selling them, which led ICS to speculate in buying and selling potatoes on Latin American potato markets. As Leo MacIsaac, ICS assistant manager for potato marketing at the time, later put it, ICS manager Jerome O’Brien was "into the potato business up to his ears" and "was a bit of a gambler, and usually won". According to MacIsaac’s recollection, O’Brien’s propensity for speculating on the market for potatoes occurred not only with the potatoes coming through the local co-operatives from its member-growers but also with potatoes from the several large, private growers on the Island with whom he was also working.67 Another co-operator from that era, Joe Gaudin, remembered O’Brien as "a very aggressive manager – a hard worker – . . . [who] would go out and buy against the other buyers instead of just marketing for the co-operative members". According to Gaudin, by June 1955, O’Brien on behalf of ICS had succeeded in buying up virtually all of the older potatoes on the PEI market at a time when there was always the danger of the new potatoes coming in and making the older ones virtually worthless. "Prices were going up every day", stated Gaudin, "and he bought thousands and thousands of dollars of potatoes, and all of a sudden, the bottom fell out of the market".68

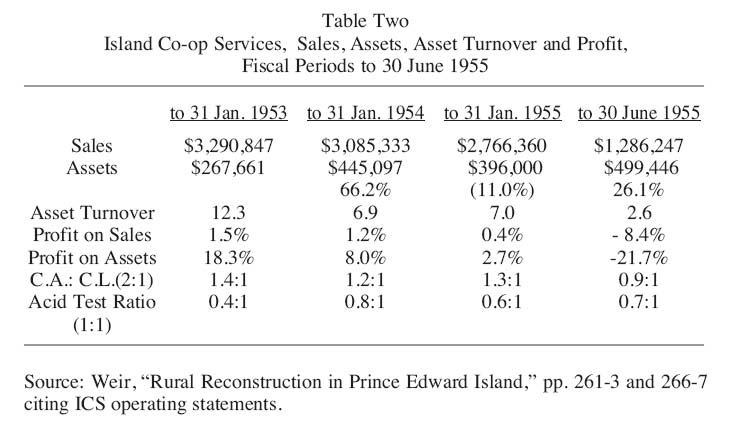

23 Both Gaudin and MacIsaac suspected that three or four of the largest private potato dealers on the Island colluded to create a temporary collapse in the potato market – leaving ICS holding several dozen railcar loads of virtually worthless potatoes (and turnips). In any case, ICS could not recover. As can be seen in Table Two, the high level of assets by 30 June 1955 combined with plummeting sales and a much slower turnover on those assets meant disastrous losses. Between 1 February 1955 and 30 June 1955 ICS lost $125,832, which, combined with ICS’ weak financial structure, particularly its lack of adequate member equity and capital as well as its inability to quickly call in any accounts receivable, meant that ICS was unable to meet its financial obligations and was forced into receivership on 12 August 1955.69

Table Two : Island Co-op Services, Sales, Assets, Asset Turnover and Profit, Fiscal Periods to 30 June 1955

Display large image of Table 2

24 The events surrounding the eventual bankruptcy of ICS lend credence to Gaudin and MacIsaac’s suspicions. A restructuring proposal for partial reimbursement, according to Joe Gaudin, was met with disinterest: "They just wanted to close everything out, sell the assets and divvy it up among the creditors".70 More telling, says Leo MacIsaac, was the fact that "after ICS went broke, and the mess cleaned up, the market became fairly good again. . . . [It was] a couple of months. Just long enough to put them out of business".71

25 By 1956 ICS was bankrupt, and Premier Walter Shaw insisted that W.H. McEwen review the Bank of Nova Scotia’s plans for liquidating ICS. According to McEwen’s biographer, Stefan Haley, McEwen was "appalled" at the bank’s plan as it "would not only have liquidated ICS, but would have sunk half the co-ops on the Island, leaving a few small unprotected stores". After several weeks of work on PEI, McEwen and his assistant Lloyd Horton were able to appease ICS creditors, and their revised liquidation plan led to the demise of ICS and only "a few highly over-extended co-ops while local co-operatives over the next few years gradually increased their dealings with Maritime Co-op Services".72 Jerome O’Brien retired from working with cooperatives and went into the potato business himself as a grower, buyer and seller; he later moved to Ontario to become a teacher. Representatives of some of the remaining Island co-operatives, worried about the lack of marketing channels for their grower-members, came together in the fall of 1955 and established Producers’ Co-operative Association, which quickly became PEI’s largest marketer of seed potatoes; by 1956 it was also involved in poultry processing, egg grading, selling wool for the PEI Sheep Breeders’ Association and feed production. Unfortunately, Producers’ Co-operative suffered from the same lack of support, patronage and capital as ICS had as well as often-successful attempts by private dealers to entice members away from Producers’ Co-operative by offering slightly more money per bag of potatoes. By late 1962, Producers’ Co-operative had suffered the same fate as ICS.73

Eastern Co-op Services

26 The two co-operative wholesales in eastern Nova Scotia – Eastern Co-op Services and Cape Breton Co-op Services – followed a similar yet different path than that of ICS when it came to the question of co-operative development. Like PEI co-operators, co-operators in eastern Nova Scotia were more than open to many new initiatives and product lines. At Eastern Co-op Services, an egg incubator was added in 1946, and the organization began to sell hardware items as well as canned goods.74 The ECS board of directors even entertained a presentation in 1948 by Mary Black of Nova Scotian Handicrafts and Alex Laidlaw of the Saint Francis Xavier University Extension Department on how the Rockland Woolen Mill in Pictou County might be disassembled and moved to the Antigonish area.75 Most significantly, in 1946 A Plan of Co-operative Development for the region served by Eastern Co-operative Services was circulated, which proposed the creation of greater co-ordination of cooperative effort through the building of co-operative cold storages and a bigger truck fleet to help transport "supplies, flour and feed" from the wholesale in Antigonish to co-ops in Guysborough County, with the trucks carrying back fish to the main cold storage at ECS for later shipment to the local co-ops and to points elsewhere in the province or beyond.76 For its part, Cape Breton Co-op Services explored the possibility of becoming involved in the oil and gas business (even hiring a new person, John Guerney, and sending him to study the co-operative oil operations in Kansas City for six months), considered how to expand the local production of poultry and eggs, and examined the viability of buying a hardware store in Sydney and of building cold storage facilities.77

27 Despite this openness to new endeavours in serving their members, and a few good years after the war, both ECS and CBCS were hard pressed to cope with the financial and other problems that they faced in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Both cooperative wholesales suffered from a lack of support from their member co-operatives as did many of the local co-operatives in terms of their individual members. At one member store of CBCS in May 1947, for instance, 560 of the 1,100 members had spent less than $2 at the co-op in the previous six months.78 There was also a lack of action taken over the proposed cold storage facilities and a noticeable decline in enthusiasm for co-operation in general.79 ECS manager Bernie MacLennan reported to the 1950 annual meeting that "we are losing the initiative down here in the East where we are wont to boast as the cradle of the Antigonish Movement and cooperation as we know it".80 For his part, Joseph Chisholm, the CBCS fieldman, lamented that co-operators seemed to forget "the ABC’s of co-operation" at a time when they should be going for their "Junior Matriculation".81

28 ECS and CBCS also suffered from serious financial problems. Both had high accounts receivables, often high accounts payable and low working capital. ECS was also plagued by a poor ownership structure; its membership consisted of ten local cooperatives, but most the business was done directly with individual co-operative member/farmers, thus providing the individual farmers with little incentive to invest more capital.82 Yet as the 1950s progressed, it was at CBCS that the situation became critical. ECS improved its annual sales slightly from 1952 to 1956 from $1 million to $1.33 million and its net gain from $3445 to $35,161.83 The same cannot be said for CBCS, as sales dropped each year between 1952 and 1956.84 Moreover, the cash position of CBCS fell by $186,525 in 1953 alone, as the wholesale opened a building supplies department without sufficient working capital. Within a year, not only had the cash position of CBCS declined a further $44,000, but MCS had begun to deduct what CBCS owed it out of CBCS’ share capital in MCS. Moreover, CBCS accounts receivable were up $53,000.85 When Sydney Co-op representatives brought forward a successful motion at the 1955 CBCS annual meeting that the wholesale should work towards amalgamating with MCS, CBCS officials, apparently unwilling to countenance such a move, delayed committee work on this matter.86

29 Circumstances, however, would push CBCS towards merging with ECS. Improved transportation within eastern Nova Scotia had prompted some co-operators in Cape Breton to contemplate closer ties with ECS, which was already delivering milk to co-ops there.87 Changes at the Saint Francis Xavier Extension Department also helped to promote an amalgamation of ECS and CBCS. The Roman Catholic bishop of Antigonish made it quite clear to Extension officials that unless Extension was prepared to do more in terms of assisting industrial Cape Breton, then he would find another group that would.88 Most importantly, a young John Chisholm was recalled from extension work in Fredericton in the early 1950s to become the director of rural development for the Extension Department. Chisholm quickly grew dissatisfied with the pace of change in his hometown of Antigonish, and he took steps to address that problem: "I came back here and things were pretty slow. . . . So I got a big chart and drew up a program of development for the six eastern counties of Nova Scotia. . . . Included in that we had the amalgamation of Eastern Co-op Services in Antigonish and Cape Breton Co-op Wholesale – there had been no connection between them and in the country there were 100-150 small stores and in the towns".89

30 Chisholm’s plan, entitled A Program of Rural Development for Eastern Nova Scotia, sought to address what he considered the major problem facing the area – the unnecessary and tragic decline of primary production (especially agriculture) in the region. Farmers and other primary producers, he asserted, had lost their markets and were threatened with the loss of their rural way of life because they had not kept up with modern trends in production and marketing. Because consumers’ tastes were increasingly favouring products which were "graded, canned, manufactured, processed or attractively packaged", the lack of "the necessary plant facilities for assembling, processing and orderly marketing" along co-operative lines was the "main reason for drastic decline in farm production over the past number of years". The consequences of co-operators failing "to adjust themselves . . . to meet the challenge of a scientific, industrialized world" had been several: the best and brightest of the young people had migrated out of the region in search of opportunities, those young people who remained quickly adopted their elders’ conservative and defeatist approach to rural life, and food was increasingly imported into the region from across Canada and other parts of the world.90

31 In order to address these problems, Chisholm’s Program of Rural Development for Eastern Nova Scotia called for a new approach based on "positive and objective leadership" instead of "mere routinists" and "mediocre leadership from our politicians right down through the line", a re-evaluation of all co-operative organizations, and a concerted effort to establish new facilities for the production of new products such as processed fish, fruits and vegetables as well as the marketing of forest products. As Chisholm stated: "This is the road to a co-operative economy – ownership and control of essential goods and services by the people on a mutual basis – such control is necessary if the rural communities of Eastern Nova Scotia are to prosper or even survive".91 Moreover, the overall goal of the plan, stated Chisholm, was "the betterment and development of human beings" grounded firmly in Christian principles because, in Chisholm’s words, "the most direct road towards a sound Christian society will be found in the development of rural life through co-operative principles". Chisholm contrasted "the distractions, exposures and temptations of a modern corrupt world" with that of the good life offered by the rural areas where "people can live Christian lives and more easily justify the purpose for which they were created". He concluded that "in this eastern area of Nova Scotia we have all the natural requirements for the development of a prosperous rural life program. We have land, markets, and people. As Christian citizens it is our responsibility to develop them to the fullest possible extent".92

32 This antimodern vision of a revitalized Christian, rural society as the desirable alternative to the "modern corrupt world" – created through co-operatively established modern marketing efforts and production facilities – is an aspect of antimodern thought outside that of Ian McKay’s conceptualization of antimodernism in Nova Scotia during the middle decades of the 20th century. McKay, following Raymond Williams in The Country and the City, allows for the possibility of antimodernism’s "Janus face, pointing to accommodation with and resistance to capitalist hegemony". McKay, though, maintains that Nova Scotia’s "precarious socio-economic position" in the 1920s and 1930s meant that its antimodernism "was much more one-sidedly reactionary" because it arose out of the advent of the tourism economy, the "silencing of many of the people who might have mounted a powerful challenge to the new antimodernist common sense" (such as "a once mighty radical labour movement") and the emergence of new, general identities such as "Maritimer" and "Nova Scotian" that were quite amenable to "the restoration of a comforting conservative ideal" as embodied in the myth of "Innocence" – that "Nova Scotia’s heart, its true essence, resided in the primitive, the rustic, the unspoiled, the picturesque, the quaint, the unchanging: in all of those pre-modern things and traditions that seemed outside the rapid flow of change in the twentieth century".93 John Chisholm’s vision of co-operative development, in contrast, embodies an antimodernism that is both backward looking and progressive – combining a yearning for a rural, pastoral "Golden Age" with an emphasis on modern marketing and technology. Moreover, Chisholm’s vision was not an isolated incident that simply arose out of his experiences in eastern Nova Scotia in the early 1950s; it grew out his rural work with the Extension Department at Saint Francis Xavier University and the Antigonish Movement’s long-standing idealization of rural life over that of modern urban life. Father Moses Coady, for instance, had for many years expounded the desirability of rural life over life in urban centres – especially "in this day of libraries and good roads" – because farming provided an "abundant life" with "not only economic and social security and the best possible moral and cultural environment, . . . [but] an opportunity for self-expression and creative thinking afforded by absolutely no other calling".94

33 The Christian, agrarianist "Chisholm Program", as it became popularly known, aroused much enthusiasm in eastern Nova Scotia. As Chisholm noted years later, the reaction of the area’s priests was instantaneous and overwhelming: "The first day I presented the program – with the little pamphlets – in the assembly room of the university – all the priests were there for some sort of meeting, and two or three bishops – almost two hundred people. I spoke for a half an hour on the program – I had the script. I got from that group a standing ovation that lasted ten minutes after I presented. Now that’s not necessarily good – there was a lot of emotion there . . .".95

34 Other people were much less impressed. R.J. MacSween, the Nova Scotia deputy minister of agriculture, for instance, took exception to the program even before he had the chance to read it; rumours of what it contained and different versions of its contents did not concern MacSween nearly as much as the fact that the whole plan had been developed "without the approval of the Department of Agriculture" and "without consultation among all concerned". Moreover, and not surprisingly, MacSween took exception to Chisholm’s characterization of the "mediocre leadership from our politicians right down through the line" as meaning nothing else but "that Department of Agriculture men are stupid from the Minister down".96

35 W.H. McEwen, the general manager of MCS, also had grave concerns about the Chisholm Program. In a detailed critique of the plan sent to Chisholm on 14 October 1955, McEwen acknowledged that "there is a great deal of merit in your analysis and in the proposals", while taking issue with several key points. He did not share Chisholm’s optimism about the agricultural potential of eastern Nova Scotia and appended to his letter an analysis of Canadian agriculture done several years before that referred to the six eastern counties of Nova Scotia as "the most seriously depleted agricultural area in Canada". McEwen also questioned Chisholm’s assumption that if facilities for processing and freezing of agricultural products were available then production would automatically follow – and pointed to the cases of Scotsburn Cooperative in Nova Scotia and its more-than-adequate poultry facilities and the abundant apple-handling facilities in the Annapolis Valley; in neither case did the creation of these facilities result in appreciably more production. Moreover, McEwen noted "I think we have to face also the fact that there is no apparent scarcity of produce, even though some of it may be coming half across the continent, or half around the world". Increased local production of agricultural goods would not only have to meet the competition of these imported goods "from areas that agriculturally are definitely superior" to eastern Nova Scotia, but local producers would also have to be prepared for the increased competition (and lower prices) that increased local production would be sure to bring. Instead of Chisholm’s approach, McEwen suggested that production, facilities and the personnel "have to develop together and no one of them should get materially ahead of the other", and so build on each other gradually.97

36 Despite this trenchant critique, the Chisholm Program proceeded with much fanfare and optimism. On 17 October 1956, Father Moses Coady, in his keynote address at the organizational meeting of the newly merged wholesale, summed up the optimism of many of the delegates when he talked about the parallel between the new ECS and the accomplishments of the Antigonish Movement years before: "Today we are witnessing a great new step in the creation of an organization that is the synthesis to a large extent of the total program that was envisioned twenty-eight years ago. This proposed new step in the organization of the people of Eastern Nova Scotia is, without doubt, the biggest single step ever taken for the social and economic development of our people here in Eastern Nova Scotia".98

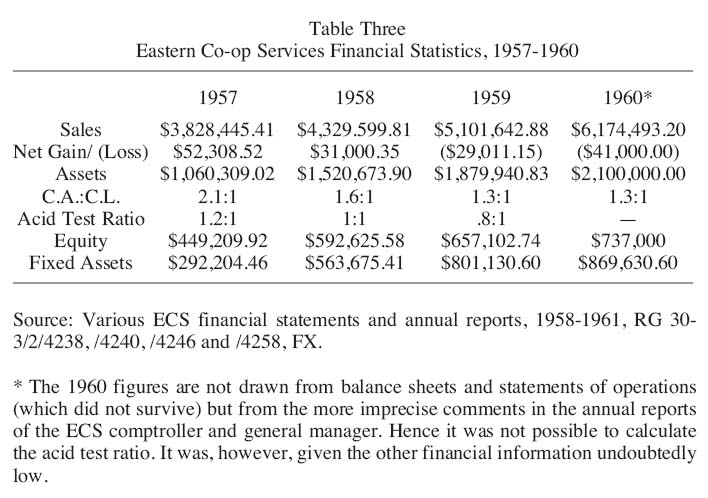

37 On 3 January 1957, CBCS merged with ECS to become the "new" ECS and, for a time, the new co-op wholesale had some success. But in less than three years, ECS was again suffering from serious financial problems caused by low amounts of working capital, a lack of management expertise, a lack of support from its member co-operatives and the heavy debts incurred by the construction of a much-vaunted agricultural plant in Sydney. McEwen’s warning about the danger of erecting processing facilities before sufficient raw material was being produced proved prophetic. Built at a cost of approximately $300,000, the "Plant", as it became commonly known, never reached anywhere near full productive capacity and lost almost $300,000 between 1958 and 1964.99 As can be seen from Table Three, although sales, assets, equity and fixed assets continued to climb between 1957 and 1960, initial net gains quickly became dramatic losses while both the ratio of current assets to current liabilities and the acid test ratio dropped far below desirable levels (2:1 and 1:1 respectively).

Table Three : Eastern Co-op Services Financial Statistics, 1957-1960

Display large image of Table 3

38 ECS was forced to go into a limited bankruptcy in 1961; only a loan of $300,000 from Maritime Co-op Services and the Credit Union League of Nova Scotia to pay off creditors kept ECS from going under.100 Despite this infusion of cash as well as the appointment of a permanent, five-member advisory committee (that included W.H. McEwen) and the departure of John Chisholm and the end of his Christian, agrarianist program of development, ECS could not survive.101 Rod MacSween, a long-time staff member of ECS, became its manager yet, despite the closure by 1962 of several money-losing operations such as the insurance department, the Co-op Irving service station and restaurant in Sydney, the cold storage depot in Margaree Forks, and the Newfoundland dairy, poultry and vegetable operations, ECS continued to be faced with heavy losses and poor prospects.102 Negotiations began in 1963 over the absorption of ECS operations by MCS, and the following year both the ECS and MCS annual meetings approved this move.103 On 1 January 1965, co-operative wholesaling in the Maritimes officially came full circle as it returned to one, Maritime-wide cooperative wholesale based in Moncton.104

Conclusion

39 The case of co-operative wholesaling in the region through to the 1960s is important in several ways. It underscores both the importance of business solvency for co-operatives that must find the means to operate and survive within a capitalist economy and the dual nature of co-operative enterprises as part of social movements and as businesses. Thus, not only does co-operative wholesaling serve as a useful corrective to the existing literature on Maritime co-operatives, which focuses almost exclusively on co-operatives as elements of social movements, but it also demonstrates that there is no clear-cut division between social movement and business in co-operatives. In the case of McEwen and Maritime Co-op Services in particular, there is a consistent thread from the 1930s to the 1950s of viewing cooperative wholesaling as the second stage of co-operative development within an enduring vision or goal of establishing a co-operative commonwealth, even though that commonwealth became more and more distant a goal as the 1950s progressed. Part of the problem was, no doubt, McEwen’s own conservative nature and those that he gathered around him.105 Although he was "a modest man with immodest ideas . . . [who] proposed nothing less than a totally co-operative economy", his focus, even pre-occupation, with financial stability and incremental growth and his identification of co-operation as the ultimate expression of free enterprise no doubt worked against MCS’ role in the realization of a radical re-ordering of society along the lines of a cooperative commonwealth.106

40 The story of co-operative wholesaling in the Maritimes through the 1950s also points to the need for a more nuanced conceptualization of both antimodernism and modernity. The antimodernist efforts by some co-operators in eastern Nova Scotia to try to preserve their rural society through a program of rural development based on technology and active participation in the modern economy is an effective antidote to the notion of Nova Scotia antimodernists as "rustic", "unspoiled", and "unchanging"; instead, John Chisholm’s efforts (and Moses Coady’s efforts before him) to use modern means to help preserve a fast-disappearing rural way of life suggests that antimodernism in Nova Scotia was considerably more complex. Similarly, the case of co-operative wholesaling indicates the need to broaden the conceptualization of modernity beyond "urbanization, professionalization and the rise of the positive state" so as to be able to incorporate the phenomenon of rising corporate concentration within the Canadian capitalist economy.

41 If the case of co-operative wholesaling demonstrates anything it is that modernity within the region was, as Daniel Samson suggests, "a contested ideological and cultural field . . . with varying ideas about progress and civilization".107 O’Brien, McEwen and Chisholm had sharply contrasting views on how best to develop their wholesales and the co-operative movement in general: O’Brien chose to let cooperative principles and loyalties slide in the pursuit of economic advantage, McEwen chose to promote incremental change and business solvency over rapid expansion of services, and Chisholm valued broader social goals such as the preservation of rural life while downplaying business considerations. Underlying the approaches within particularly MCS and ECS, however, was the voluntarist notion that if co-operators tried hard enough – if they had the necessary "faith, courage and determination" – then they could achieve their objectives.108 The profound societal changes in the region, though, particularly during the 1950s, point in a different direction. Rapid rural depopulation and outmigration, further inroads from an interventionist state in terms of social welfare measures, the state’s extensive support for and collaboration with capitalist enterprises, and rapid economic concentration and improvements to transportation meant that co-operatives faced a much different situation than in the 1930s. Even if co-operatives in the region had managed to resolve their many internal problems such as the local co-operatives’ lack of patronage of the wholesales and individual co-operators’ lack of loyalty to and investment in the local co-ops, the systemic social and economic changes wrought by modernity and economic concentration would have, no doubt, largely mitigated against the creation of a "cooperative commonwealth" or even the widespread economic democracy envisaged by Moses Coady. The inability of larger and more successful co-operative wholesales elsewhere, including the Canadian Prairies and England, to create and sustain a "commonwealth" suggests that there were profound difficulties facing co-operatives in trying to establish such a vision to counter the concentration of power and resources within capitalist modernity.

42 By the 1960s, McEwen had apparently abandoned his lengthy quest for the Promised Land of a co-operative commonwealth. No doubt disillusioned by the demise of ECS and ICS and the inability of Maritime co-operators to engage in unified co-operative action, one of the last surviving regional co-operative leaders whose formative years of work had been during the crucible of the Great Depression retired as general manager of MCS in 1962. Even though he stayed on for several years as secretary to its board of directors, it is clear that he recognized that a new phase had arrived in the development of co-operatives in the Maritimes. In his 1969 Faith, Hope and Co-operation: A Maritime Provinces Story, his memoir of the evolution of Maritime Co-op Services, he noted "these changing times brought the need for new and more aggressive personnel at the management level" and concluded that the development of MCS up through the years, with its accomplishments and undertakings in a wide variety of enterprises, justified the faith and hard work of all of the members, employees and boards of directors: "The results have been good enough so that the originators could say that their efforts were worthwhile" and that all those involved in the organization, through their "faith, hope and energy, provided the Co-operation that has made this business grow, and to become ever more important in the business world in which it operates".109 The Promised Land must have seemed far off indeed.

Notes