Globalization, Glocalization and the Canadian West as Region:

A Geographer's View

Randy William WiddisUniversity of Regina

1 THE TRADITIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL CONCEPTS of region, boundary, place and territory play prominent roles in the current debate about globalization. Many have argued that recent processes of globalization and capitalism are weakening borders and undermining the traditional Westphalian nation-state system of organization, territory and identity. Indeed, some assert that these elements, or at least a few of them (especially territories and boundaries), are losing their traditional meanings as a consequence of the increased spatial interaction and flows of capital, people, goods and information. Conversely, others cite evidence to suggest that the development of new technologies has in a variety of ways increased the need for highly specialized regions, places and localities for the production and use of those technologies. They argue that underneath modern consumer culture there exists a significant, and perhaps increasing, degree of localism.

2 In light of this debate, those who make region the focus of their work are obligated to address questions about the meaning of the term "regional" in a world in which borders, we are told, are becoming increasingly meaningless. In this paper, I will offer a few reflections on place, identity, territory, boundary and region; I will then move on to a short discussion of the problems scholars face in defining the West as a region and conclude with a deliberation on the "place" of the Canadian West in the debate over globalization.

Place, Identity, Territory, Boundary and Region

3 "Place is space to which meaning has been ascribed" (Carter, Donald and Squires, 1993, p. xii) and "place is seen as the foundation of identity" (Eyles, 1985, p. 72). Identity develops as people engage in "place-making" – the way all of us as human beings transform the places in which we find ourselves into the places in which we live (Schneekloth and Shibley, 1995, p. 1). Identity is often manifested spatially and, in this context, the territory ascribed to identity is demarcated by boundaries, however real or imagined. Indeed, the nation-state is predicated on the idea that geographical borders, by symbolically differentiating "here" from "there", delineate belonging. Much new work in critical geopolitics deals with questions associated with the idea that borders are political representations of power and, as such, have a great deal to do with the spatiality of self, identity and state (Ackleson, 2000). And while the foundation of all codes of collective identity is built upon the distinction between "us" and "others", these codes are connected in various discourses with other social and cultural distinctions such as core-periphery, past-present-future or inside-outside, which, in turn, may be designated as the spatial, temporal and reflexive dimensions of coding (Eisenstadt and Giesen, 1995).

4 While place, territory, boundary and identity are considered as ideas unto themselves, they are all relevant to the notion of region, which is, arguably, the most important concept in geography. Region has been a major source of identity for geographers, a key instrument of classification and a major conceptual tool in developing diverging approaches in geographic research. Traditionally, regional geography was characterized "by a synthetic view of the world, i.e., it tried to put things together in a regional context, and by the epistemological conviction that it needed to view the world as a mosaic of idiosyncratic, singular entities – the regions" (Wood, 2001, p. 12908). It included an understanding of both physical and human geography and how the blending of those elements in an area produced regional character.1

5 By the 1960s, a nomothetic discourse became the mainstream methodological underpinning of geography. Geographers, heavily influenced by logical positivism, attacked regional geography for its emphasis on uniqueness and its neglect of processes underlying observed patterns. Focusing on the spatial variable and the study of spatial systems, geographers made distance, accessibility, agglomeration, size and relative location the five qualities relevant to building spatial theory designed to systematically explain spatial interaction. As a consequence, the regional concept was relegated to a secondary position although not for long. Many geographers became dissatisfied with the excesses of the spatial paradigm and, influenced by structuralist and humanist perspectives, increasingly argued for a reassertion of region into geography. A new, reconstituted regional geography resulted, one premised on the assertion that global change is produced and experienced at the local level.

6 Unlike earlier chorologies, which focused on the differences in arrangements of physical and human phenomena that determine the unique character of specific localities, this new regional geography portrays regions not "as static, ahistorical units, but as the products of local actors situated within a wider division of labour" (Warf, 1988, p. 342). Gilbert (1988, pp. 209-13) identifies three concerns that distinguish the new regional geography:

- A concern with regions as "local responses to capitalist processes"

- A concern with region as "a focus of identification" (or "sense of place") and

- A concern with region as "a medium for social interaction", playing "a basic role in the production and reproduction of social relations" [italics in original].

7 Despite its renaissance in geography, the concept of region is still subject to debate. All regions are, to some extent, human constructs and, wherever identified, are subject to criticisms about the criteria upon which they are based. For some geographers, there is concern that region is too descriptive an instrument and, as a result, can be defined and constructed according to the needs of the individual scholar. Since each region is part of and reacts to larger processes and interactions, it is prone to a constant state of change that only makes its conceptualization more difficult. Also, any regional schema, no matter what the scale, is a generalization and will not always be the appropriate spatial unit for examining interactions taking place within specific areas. Thus, the great irony for geographers is that while they acknowledge the challenging issues associated with the concept of region, they are nevertheless compelled to consider its role – as well as that of related concepts such as place, territory, boundary and identity – in the lives of human beings.

The Canadian West as Region: problems of definition

8 In light of the preceding discussion, it is important for scholars to question the criteria they use to define the Canadian West. Too often it is portrayed as some kind of amorphous region, given unity by dominant physical characteristics, hinterland status, settlement history or other features that hide the complexity of this part of Canada. If one accepts the argument that regions are evolutionary entities which are historically and geographically constructed, and that meanings connected to them are constantly changing along with developments taking place both externally and internally, it is appropriate to question the traditional criteria used to demarcate all regions, including the Canadian West.

9 The physical environment often plays a significant role in peoples' perceptions of region and, in this context, many people perceive western Canada as a region dominated by a horizontal and monotonous landscape. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth as the West has numerous distinct physical environments besides that of the prairies. Even the prairies, a subdivision of the West, which is arguably the most uniform and identifiable formal physical region in the country, varies greatly in terms of climate, topography, vegetation, soils and wildlife, and geographers apply various concepts such as ecozone, ecoprovince, ecoregion and ecosection to illustrate the regional variety of physical environments in the western provinces.2 The basis for the traditional definition of the West and even that of the Prairie West – the physical environment – is not, and never has been, adequate (Wardhaugh, 2001, p. 7).

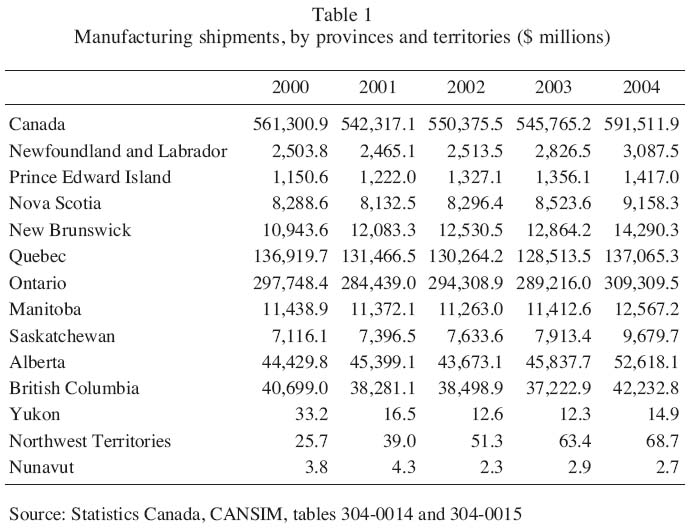

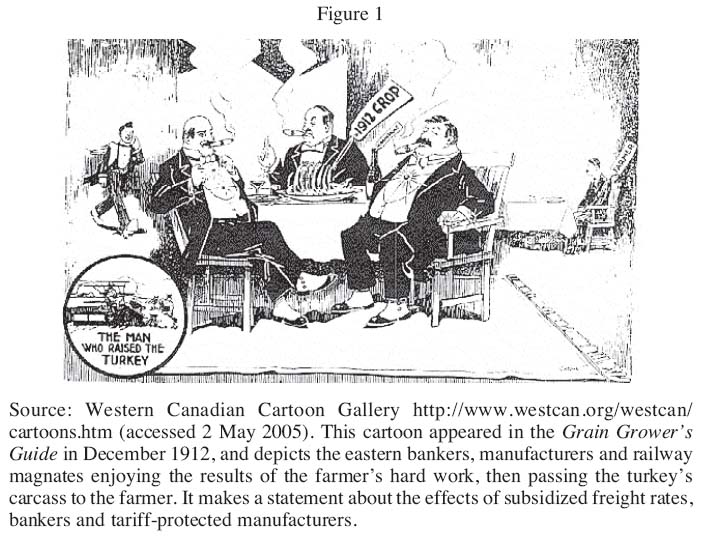

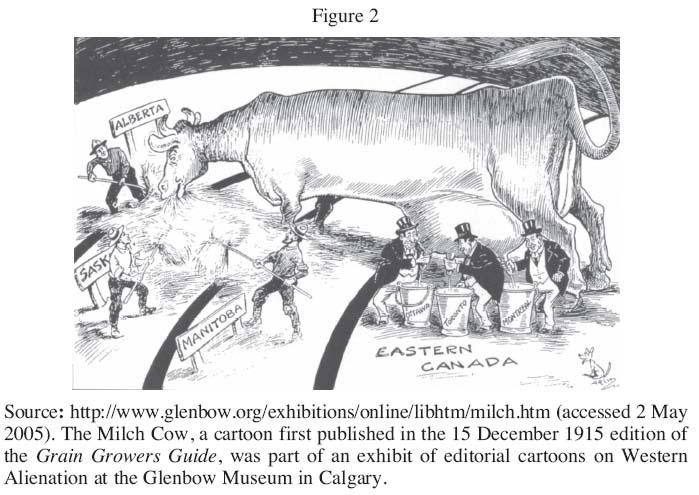

10 A central tenet of geography is that location is essential in understanding a wide variety of processes. In just about every facet of life, location matters and this is certainly the case for western Canada. In an insightful essay on the problems inherent in defining the Prairie region, Gerald Friesen (2001, p. 14) refers to Cole Harris's (1981) argument that Canadians apply broad regional generalizations such as the West, Central Canada, the East and the North not only to interpret their identity vis-à-vis the rest of the country, but also to establish a spatial platform for various grievances they have towards the federal government. Social and geographical isolation has historically played a role in the development of this region. The West's relative location far from the largest markets as well as the exploitation of its resources by eastern capitalists supported by the protectionist National Policy of tariffs, railway subsidies and land policies helped ensure that Central Canada would be the focus for manufacturing while the rest of the country would produce grain, lumber, fish and cattle for domestic and world markets (figures 1 and 2). Yet the hinterland status that unified the western provinces into a larger economic area over a century ago is less relevant today in those parts of the region, particularly Alberta and British Columbia, that have used their rich resources and links with foreign markets to diversify their economies (Table 1). The metropole-hinterland relationship that lies at the heart of this definition of the West as region is both more fluid and more dynamic than such a functional classification would suggest. The fact that notable economic differences exist in the modern Canadian West based on the uneven distribution of resources and the consequential irregular development of industries prompts us to question the traditional definition of Canadian regions based on relative location within the country and the conventional heartland-hinterland paradigm.

Table 1. Manufacturing shipments, by provinces and territories ($ millions)

Display large image of Table 1

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM, tables 304-0014 and 304-0015

Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Source: Western Canadian Cartoon Gallery http://www.westcan.org/westcan/cartoons.htm (accessed 2 May 2005). This cartoon appeared in the Grain Grower's Guide in December 1912, and depicts the eastern bankers, manufacturers and railway magnates enjoying the results of the farmer's hard work, then passing the turkey's carcass to the farmer. It makes a statement about the effects of subsidized freight rates, bankers and tariff-protected manufacturers.

Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

11 History is a resource that is often used by people to construct regions, whether real or imagined. Yet history testifies to the significant diversity in the peopling of this region. As Friesen (2001, p. 17) contends, the functional and imagined regions in pre-contact Aboriginal societies do not coincide with the present-day boundaries of the Canadian West. Environmental, social, cultural and economic diversity produced vastly different societies and cultural regions, ranging from the fishers of the Pacific coast to the hunters of the prairie grasslands. European settlement of British Columbia differed considerably from that of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba and, even within the three Prairie Provinces, the variety of ethnic groups that settled this area ensured a substantial diversity of experiences and micro-regions. The resultant convergence of Native peoples, European immigrants and North American-born colonists (not to mention the different experiences of women and men) and all of the multiplicity of interactions with the natural environment was not, however, unique to the West. This same process happened elsewhere in North America and so does not stand out as a defining characteristic of this region. Changing relations between rural and urban sectors and Natives and newcomers, the growing power of provinces and individual cities in national politics, the dissimilar nature of recent migration patterns (the most notable being the significant influx of Asians into British Columbia and the large flow of other Canadians into Alberta) and the revolutionary impact of technological changes in culture and communication have all served to erode the similarities that created unity within such a large area and exacerbate the geographical, economic, social and cultural differences that have existed for a considerable time. It is also important to recognize, building on the revisionist impulse of the last two decades, that historical interpretations of the West as region differs between those who consider the past from the point of view of the colonized and those who reflect on history from the point of view of the colonizer.

The "Place" of the Canadian West in the Debate over Globalization

12 The Canadian West is a regionally diverse entity made up of many different wests, some of which have been in existence for quite some time while others have only emerged just recently. Geographical conditions of postmodernity, marked by "an intense phase of time-space compression" (Harvey, 1989, p. 284), point to the temporary nature of regions as geographical features. This, in turn, has prompted some scholars to wonder whether or not regions, if they actually existed at all, have been extinguished by globalization. Globalization bends and stretches borders out of "regional" shape and creates new transnational spaces that "shatter old notions of regions" (Wardhaugh, 2001, p. 7). Conventional borders, it is argued, are disappearing in a situation of postmodern territoriality, and new technologies are resulting in the destruction of regions and places. Globalization is seen as involving a complex "de-territorialization" and "reterritorialization" of political and economic power.

13 Contemporary theorists such as Appadurai (1996) and Bhabha (1994) tell us that we are all borderlanders and, because of this fact, borders are largely inconsequential. For Appadurai, nation-states and, by implication, regions and borders, are increasingly irrelevant in a postmodern, post-colonial and soon to be post-national world where electronic communications have resulted in networks replacing traditional geographical spaces as the major frames of affiliation. Bhabha believes that because we all are liminal beings – that is, we all are interstitial creatures living in spaces of "in-betweenness" – the traditional notion of territory and associated identity as defined by borders is no longer pertinent.

14 While Appadurai emphasizes the emergence of "sovereignty without territoriality", others maintain that nation-states will continue to occupy an important place in people's lives even as regionalization based on economic and political associations (e.g., the European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement) result in a gradual changing of the territorial state (Anderson and O'Dowd, 1999). The term "glocalization" is used by some to conceptualize a process whereby sub-national – that is, local and regional – and super-national actors interact, circumventing the national level in-between (Blatter, 2004, p. 530). Many believe that "local economic development is increasingly a regional phenomen[on] [and] regional ties are just as likely to cross national as local borders" (Reese and Fasenfest, 2000, p. 355). Glocalization also acts intra-nationally, linking specific communities, groups and governments with other similar units across provincial and hierarchical borders. Such processes of glocalization suggest that Canada is no longer just a partnership of the federal government and the provinces; local governments and Aboriginal governments are also quickly emerging as important partners in the governance of the country.

15 So the question remains: where does the traditional idea of the Canadian West as region fit into this discourse? While Friesen (2001) contends that the Prairies as region has lost its relevance in light of changes taking place both from within and from without, he argues that there are strong grounds for the creation of a functional political region, a "political West", that transcends the differences existing between the four constituent provinces and numerous metropolitan centres. This region, he argues, is not yet fully imagined, united or uniform, but instead is functional – serving as a political space that articulates the voice of that part of the country west of the Lake of the Woods (Friesen, 2001, pp. 24-5). While his argument is compelling and even persuasive in some respects, it is still, by and large, unconvincing if only for the fact that it assumes that the media and popular culture have produced a western political viewpoint that transcends sub-regional differences. The political viewpoint speaking for the West, he contended in 2001, was that of the Canadian Alliance, a political party no longer in existence because it was too strongly identified with Alberta and seen to be too removed from many other parts of the West, let alone the rest of Canada. The West is not a single political entity with a common political culture. If we just consider the political histories of Alberta and Saskatchewan, the former has been governed for much of its history by governments that are either conservative or Progressive Conservative, while the latter's most prominent governments have been social democratic in nature. A shared political vision does not serve as a centripetal force within the region; rather, it is identification with a larger entity that juxtaposes itself against another part of the country that traditionally has been the centre of power that acts to unite people.

Conclusion

16 Borders matter; they always have and they always will, despite what globalization theorists tell us. People crave definitions, and borders serve to define territory and thus articulate identity. While it is true to some extent that the postmodern world erodes borders, it is also the case that myths, imagery, group identity and sense of place act to strengthen local and regional continuity. Western Canadians are no different than anyone else in that while they identify most strongly with community they are, paradoxically, increasingly interacting with individuals, groups, organizations and institutions located elsewhere. In a world where globalization and glocalization forces are functioning simultaneously, the West serves as an intermediary region, a "mesoregion" if you will, that bridges the identity gap existing between affiliation with both the local and the national. As stated earlier, identity is often manifested spatially and, in this context, the West as region symbolically differentiates "here" from "there",i.e., the rest of Canada (particularly Central Canada), and in this way helps people from this part of the country orient themselves territorially. This identification with the larger entity is not primarily political, at least in terms of association with one dominant philosophy. Rather, it is a historical and geographical connection that transcends time and space and continues to serve as a psycho-spatial foundation for people who live outside Ontario and west of the Lake of the Woods.

RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS

University of Regina

References

Ackleson, J. (2000, March 14-18). Navigating the Northern Line: Discourses of the U.S.-Canadian Borderlands. International Studies Association, 41st Annual Convention, Los Angeles, CA.

Anderson J. and L. O'Dowd. (1999). Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance. Regional Studies, 33, 593-615.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: cultural dimensions of globalizationMinneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bhaba, H. (1994). The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Blatter J. (2004). "From Spaces of Place" to "Spaces of Flow"?: Territorial and Functional Governance in Cross-Border Regions in Europe and North America. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28, 530-548.

Carter, E., J. Donald and J. Squires. (1993). Introduction. In E. Carter, J. Donald andJ. Squires (Eds.), Space and Place: theories of identity and location (pp. viixv). London: Lawrence and Wishart..

Eisenstadt, S. and B. Giesen. (1995). The construction of collective identity. Archives Européennes de Sociologie, XXXVI, 72-102.

Eyles, J. (1985). Senses of Place. Warrington, UK: Silverbrook Press.

Friesen, G. (2001). Defining the Prairies: or, why the prairies don't exist. In R. Wardhaugh (Ed.), Towards Defining the Prairies: Region, Culture, and History (pp. 13-28). Winnipeg: The University of Manitoba Press.

Gilbert, A. (1988). The new regional geography in English and French-speaking countries. Progress in Human Geography, 12, 208-228.

Harris, R.C. (1981). The Emotional Structure of Canadian Regionalism. In The Walter L. Gordon Lecture Series 1980-81: Vol. 5. The Challenges of Canada's regional Diversity. Toronto: Canada Studies Foundation.

Harvey, D. (1989). The Condition of Postmodernity. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Reese L. and D. Fasenfest. (2000). Introduction: Border Crossings: Local and Regional Economic Development on the U.S./Canadian Border. International Journal of Economic Development, 2, 355-359.

Schneekloth L. and R. Shibley. (1995). Placemaking: The Art and Practice of Building Communities. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Wardhaugh, R. (Ed.) (2001). Towards Defining the Prairies: Region, Culture, and History. Winnipeg: The University of Manitoba Press.

Warf, B. (1988). Regional Transformation, Everyday Life, and the Pacific Northwest Lumber Production. Annals, Association of American Geographers, 78, 326-346.

Wood, G. (2001). Regional Geography. In N. Smelser and P. Baltes (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 12908-12914). Oxford: Elsevier.

Notes

1 Geographers traditionally have classified the world into formal and functional regions. The formal region basically subdivides the landscape on the basis of discrete cultural or physical traits. The functional region is defined on the basis of complementary exchange rather than uniform traits. In this approach, regions are envisioned as spheres of social and economic interaction linking prosperous, densely populated cores to their poorer, resource-supplying hinterlands.